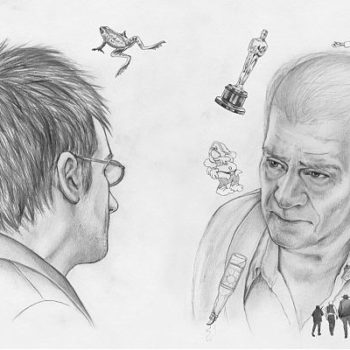

by Cheryl Cardiff

illustrator Carolina Melis

Issue VIII

TAG 1: ANKUNFT AM FLUGHAFEN / TRANSFER ZUM HOTEL UND EINCHECKEN

Herr Bruno Schlink of the former East German burg of Pfaffenheim, long-retired machinist of the Carl Zeiss Fabrik, along with his faithful wife of almost fifty years, Eva, and their grandchildren Willy and Gitte, stepped off the airplane into the Land of the Tsars. The only thing was, the place didn’t look that way to them. Willy was especially disappointed. He was expecting a cavalcade of horses with fierce looking Mongols wrapped in suedes and furs to greet them. Little Gitte raked back with her hand the wisps of blond hair that had gotten tangled with her near-white eyelashes. She looked around. Though excited, she didn’t really know where she was.

The Schlinks were fielded into a white tour bus. Bruno made a note of giving an amiable nod of his head to each person he passed, the Wessis especially whom he had spotted before on the airplane. They nodded back, eyes coolly sweeping over his face. He passed by a woman who seemed not much older than Eva. She was accompanied by a younger woman with graceful hair and eyes. Another woman who seemed to be traveling by herself was setting aside on the seat next to her the straw-colored summer hat she’d been wearing.

The bus made its way through the back streets of Sankt Petersburg, formerly Leningrad, which formerly before that was Sankt Petersburg too—this their tour guide explained. She was a woman of apparent reserve and confident high German, with hair as coppery as her complexion. She introduced herself as Natasha Petrova. Driving through the wide Nevski Prospect, the tourists slowly hit upon what was amiss from the entire scene around them. Sensing their discomfort, Natasha Petrova, without skipping a beat, continued in her cheerful way of talking. “You may be noticing at this moment how quiet everything is. On the weekdays, the Nevski Prospect becomes a vibrant, exciting place full of cars and buses and shoppers and businessmen. Sundays are traditionally spent at home with the families. Which is why everything seems dead quiet right now.” Dead quiet was right. Save for the sobering size of the granite monuments and maybe the ghosts of those revolutionaries still residing in them, the streets were entirely dispossessed of the traffic of life.

Bruno chuckled to himself. Then, he elbowed his wife softly as if to say, “These Wessis, always jumping to conclusions. Why do they even bother coming?” Eva warned him to behave.

Their bus drove up to a great grey monolith of a structure. It was the hotel where their group would be staying. Natasha Petrova explained that it was imperative for all of them to remember that they were staying in Block II and not Block I, which was a building situated clearly on the other side of the hotel where they would be housed.

Their rooms, though sparsely furnished, were clean and practical, with fresh, clean sheets on the beds and their own WC and shower. Bruno and Eva decided to divvy up Willy and Gitte between them—no use tempting fate with such excitable children. Willy was to stay in one room with him, little Gitte with Eva in another. While the old man unpacked their clothes, his grandson checked their itinerary of activities, his plump finger guiding his reading of the passages. In Willy’s other hand, a guidebook of Sankt Petersburg, which he paged through studiously.

“You know those children out there, Opa?”

“Yes? What about them?” Bruno asked, recalling the children he saw earlier who circled like peeping chicks around the woman with the straw hat. She had spoken with them in Russian as she promptly deposited a wrapped piece of candy into the children’s impatient hands.

“Were those beggar children, Opa?”

“I don’t know. I suppose so,” he replied.

“They looked just like me and Gitte, those children. Not at all like the Gypsy ones back home.”

He caught the boy’s genuinely surprised face, its transformation from discovery to empathy. How much the world had changed from when he was young, Bruno thought to himself then. He never expected that there would come a time when a boy would be surprised at the sight of children who not only looked like him but also spent their days begging on the streets. But here was that time now, in the form of his grandson, Willy, whose sudden realization cast a pall on his cherubic face.

“Are they that way because of what we did to them in the war?”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean those children that we saw. Are they that way because of the war?”

“Oh,” Bruno smiled, laughing a bit. “No. Those children are long gone. Probably grown up by now, with families of their own. The ones we saw earlier are different. They’re just poor.”

“But you’d never think that just by looking at the grandness of this place, would you, Opa,” the boy continued.

“No. You’re right there,” Bruno responded with a nod.

Children nowadays were certainly different from when he was young. They were different from when his own son, Willy’s father that is, was still a little boy. Bruno and Eva had lived through the devastation of the war. To it, he had forever lost his only brother, Rudi, who had come back from Russia, drawn and haggard, six years after the war ended. He lived still so frightened that he looked as if he wanted to withdraw even further away from the vast openness of the world and into his clothing.

Bruno inhaled with deep satisfaction. In his grandchildren lived his hope of a generation of Schlinks who would never suffer as he had, and to some extent as his own son had. Willy was an intelligent, compassionate boy of nearly eleven years with a lively interest in the world and the people in it. To Bruno’s thinking, Willy was destined for great things. Who would have ever thought that of a grandson of a butcher’s son?

TAG 2: STADTRUNDFAHRT – ISAAKSPLATZ / SCHLOSSPLATZ

Come suppertime, they returned to dine in the hotel restaurant (“Pek-toh-pah,” Gitte read out loud slowly, “I really don’t know what that means”). It was a place that looked to be a stateroom of sorts at one time. Walking into it was like entering a dragon’s belly. It was a room so different in comparison to all that they had seen in their lifetimes. It was lavishly decorated with mirrors and lighting that glowed like copper, red tapestries draped from floor to ceiling. Supper was a huge affair of soup and eggs and a rich stew. Far more sizable than what Bruno and Eva were accustomed to eating back home. A small dinner of soup. A salad of beans and greens. Rye bread and slices of ham fresh from the butcher. Here, they were like dignitaries. Rich food. Five course meals. Bottles of Coca-Cola at each table—something Willy and Gitte liked particularly. There was even a waiter carting around a grand silver and gold samovar, politely bowing as he asked the diners at each table whether they wanted any tea or more hot water with their meals.

Bruno’s stomach felt uneasy his first and second nights in Russia. Eva told him, “You’re not twenty anymore, Herr Schlink, thinking you can pack away all that rich food into your system.” Then, she laughed like a young bride at his foolishness, her face breaking out into color and unforced smiles. It occurred to Bruno that it had been a long time since he had seen Eva laugh so freely and easily. So in fact it would seem like this trip would do the both of them great good after all.

It was a trip they had planned months in advance. A perfect time to take Willy and Gitte along with them too since they would be out of school in the summer. Then, some sad news struck them not soon after they bought the tickets. Rudi had died of an embolism in his sleep.

It didn’t seem to them appropriate anymore to be looking forward to a trip to some fancy destination, and the idea of Sankt Petersburg was no more. But one day—they were having their usual afternoon coffee and cake at the time, quietly enjoying the day and the peace that brushed through the spring flowers growing along the border of their garden—Eva sighed.

“We should go,” she told Bruno. “God only knows how much time we have left to spend with the children.”

Bruno hadn’t expected her to change her mind. He looked at his wife then, the sadness in her expression. It was as if she had decided that she couldn’t continue to understand anymore why life’s course ran the way it did.

TAG 3: BESUCH DER EREMITAGE / TIKHVIN FIREDHOF / EINE ABENDVERANSTALTUNG (BALLETT)

On the third day of their trip, Bruno decided he didn’t much care for six of the people in his tour group. They were from Lübeck. They remained a tight gaggle of people from the time they arrived in Sankt Petersburg. Bruno found them arrogant. They also were ill dressed for older people, he thought, running around in tracksuits and running shoes as if life were a football event. He shook his head at this sign of disrespect. His grandchildren dressed better than these wrinkled looking teeners. On top of that, the way they spoke down to Natasha Petrova, as if she were a nobody to them, unnerved him.

Today, for example, one of the husbands, feeling adventurous, had decided to do his own sojourn through the city, after which he was to rendezvous with the group at the Winter Palace. At the expected hour, he didn’t show up. Immediately, his wife grew worried. With each minute that passed, with still no husband turning up, the wife looked close to wailing.

“You really mustn’t worry,” Natasha Petrova consoled. “The trains here are very good. They run on schedule and without fail. I’m sure he’s on his way over right now as we speak.”

“I don’t know. My husband was in the military. I’m just so afraid he may have been, you know,” the wife hesitated to say. She held out her arms rigidly before her in fists, her wrists tight together. “Slapped with the handcuffs.”

“Oh no. Nothing like that would happen,” Natasha Petrova said, dismayed that the wife could even think that.

It was then that Gitte piped up excitedly.

“Oh, but he’s right there already. Look. Isn’t that your husband?”

It was in fact the husband running up to them, flushed and sweaty as if he had just competed in a marathon. He explained breathlessly that he had lost track of time and ran the flights of steps down to the recesses of the Metropole. But he missed the train anyway. As the man told his story, Bruno’s grandchildren were jumping up and down, cheering his return.

Bruno thought to sit Willy and Gitte down and speak to them about what had just happened. Eva changed his mind.

“We’ve all been having such a good time, Bruno. Do you really want to spoil it? Besides, we’re not the only tour group of people that woman has to contend with. Last week was a different group of people and next week will be another. She by now must be so used to people becoming hysterical at the drop of a hat, don’t you think?”

“Yes,” Bruno relented, “I suppose that you’re right there.”

It turned out that Eva was right. Now, back at the dining room of their hotel, he watched Natasha Petrova gaily chatting with their tour bus driver and two other guides. Across from them sat the people from Lübeck, lively carrying on a conversation, seemingly now unencumbered by history and lingering prejudices. Eva patted his arm heartily, as if to say, “See? Does she still seem still upset to you?” Bruno gave her a nod. His wife was right. Perhaps he had been too sensitive about the whole episode.

There was only one other family of four people besides the Schlinks in their tour group. The family was made up of a man and his Asian wife, a boy and a girl with them. Teenagers. Also both Asian. They carried on with each other so convivially and so intimately that it seemed to him a mistake to think that those two young people weren’t the man’s own children.

He had met the couple earlier, starting down the corridor toward the elevators. He had come upon these two people who immediately smiled in recognition of him and began talking to them. Talk, Bruno Schlink laughed again at his embarrassment, if one can call it that. Anyway, he inquired whether they had any information regarding the times and destinations for the next day’s trips. The American and his wife merely smiled at him with a faintly bemused but nevertheless accommodating kind of look. They didn’t say a word in response to Bruno’s questions, and it slowly occurred to him that they may not have understood a word of what he said. Amicably, the couple began to speak, in English, which the old man understood about as well as the couple did his German. But moments later, the couple’s daughter appeared, and it was to her that the couple began to talk and gesture, pointing to Bruno, to whom the girl promptly turned and, in near perfect high German, made her parents’ apologies.

Only in America, Herr Schlink chuckled to himself as he rode the elevator down alone.

He watched now as the American stood up and began to collect the Coca-Cola bottles from his table, grabbing the necks with one generous hand so that it looked like he was holding an upside down bouquet of glass. He left his family and headed over to where Natasha Petrova sat. He then stood the bottles on her table, smiling and gesturing something of the sort that the bottles were for her and her group.

Bruno Schlink hoped to catch the gentleman’s eye so that he could wave hello to him. Those would be the kind of people that he would want his grandchildren to meet, he thought. He already fantasized embarking on a great friendship with this family, perhaps even visiting them one day in America and staying at their home. Or if they couldn’t all go together, well, he and Eva would scrape together enough money to send Willy over there where the Americans could then sponsor him. It was possible. He had heard of such things happening. But Herr Schlink was unable to reacquaint himself with the Americans that night. They disappeared soon after dinner and didn’t show up for the tour bus ride to the Mariinski, where the ballet performance of “Swan Lake” was going to be held. It was all that Gitte thought about, all that she kept talking about as she skipped through the cemetery of the city’s favorite sons and other beloved dead and danced around without a care in the world.

TAG 4: AUSFLUG NACH PETERHOF

On the fourth day of their trip, light rain fell over the streets of Sankt Petersburg. But even over the Neva waters the sun was already trying to break its way through the black and grey clouds. By this time, some of the people in the tour group felt so familiar with the downtown scene of the Nevski Prospect that they were deciding to splinter off and go on their own private sightseeing tour of the city. The Americans and the woman whom Bruno Schlink had seen that first day handing out candy to the Russian children stepped out of the bus.

“What about us? Aren’t we getting out?” Gitte asked.

“Shhh. Be quiet, Gitte,” Bruno overheard Willy tell his little sister.

“But I don’t understand where they’re going. Why they’re going. Why can’t we get off, too?”

Willy placed his hand over his sister’s to tell her to keep quiet.

There really was no reason why they couldn’t go and spend a day away from their group, Bruno thought. They had already seen the things that they had wanted to see and a few nice surprises besides. They had driven by the place where Rasputin staggered around and died. They had gazed in awe at the St. Isaac Cathedral (“Fourth largest cupola construction in the world,” Natasha Petrova had said proudly) that stuck out like a gigantic, elaborate silo in the midst of the city. They had seen the Bronze Horseman, as the Russian poet, Pushkin, had called the monument to Peter the Great. They had taken a picture of Willy, standing proudly like a soldier next to it. They had walked through the markets and seen their fill of circus performers. They went to a ballet and heard a concert. They had seen so much, their senses stimulated to the brim, that they fell like trees on their beds by the time they returned, so exhausted were they from each day’s journey. A respite from all that certainly would have been in order. And yet, despite their complaints of fatigue, not one of the Germans in the bus wanted to leave. With apprehension and some envy on their parts perhaps, they instead watched the five others from their group, the Americans and the Russian woman, disembark and lose themselves in the flow of pedestrians.

Maybe Willy knew a little of what was going on, Bruno thought, which was perhaps why the boy looked at his grandparents and smiled at them as if to say that he understood. The old fear still gripped these Wessis. The misadventures of that one man who had lost track of time had been a lesson to them all. None of them would ever think to leave the tour group or the cocoon that was their tour bus, which was in a way their little, secure traveling plot of Germany with the insignia of the Mercedes-Benz factory acting like a talisman.

In Herr Schlink’s case, however, there was no more that old uneasiness toward the State that had over a course of thirty years ruled what had been his homeland. But in its stead came the uneasiness of now having to live under that new cloud of disgruntlement, which rose after the dust from that crumbled wall settled. Bruno Schlink could detect that in the civilized demeanor of those six people he disliked. In the way they hardly spoke to him and Eva or, as the Americans had done, at least acknowledged him with a hello. Riding the elevator with them, he could feel the weight of their prejudices, their sense of superiority and Western impudence on his aging shoulders. German, yes, but not completely, not really.

He would not have minded taking a pause from today’s scheduled outings. But doing so, he felt, would cause unnecessary talk, incite the West Germans in the bus to nod their heads and think, “Naturally. Typical. Of course. This is why they can never be like us. It’s deep in the blood at this point. In the mother’s milk so to speak.”

As he searched for the Americans and the Russian lady in the crowd, a thousand-year-old sigh rose from his chest.

Earlier today at the Summer Palace, he and Eva had enjoyed watching their grandchildren playing with the Russian children there. The sight of them filled him with hope. He was so moved by the children’s earnestness to find quick friends in each other that he found himself searching every one of his pockets for a handkerchief.

One must sacrifice many things of one’s self if ever change for the better is to happen, he thought. Desires, wishes, what have you. There were his grandchildren to think about. They were the ones who made Bruno Schlink remember his purpose. None of this East-West nonsense for them, he determined. And so stay in the bus with the Wessis they did.

TAG 5: BESICHTIGUNG DES KATHARINEN-PALASTES / PAVLOVSK

The rain clouds came and went without so much as a drop of water to ruin their trip. Once more, they drove through the city after they had lunched at the hotel they’d been staying in for the past five days. And they sleepily listened to Natasha Petrova drone on now about the monumental statues of men and women led by Lenin that they had seen on their first day.

“Many people have asked what is to be done with these statues. Whether they are eventually going to be taken down and dismantled,” her voice came through the speakers. “But we feel that keeping them is the only way we can both remember the past and hopefully avoid the mistakes that have been made.”

They drove further out, through the suburbs, some parts of which looked like the ones back home. They went out to the countryside, toward another palatial residence where they could walk the grounds, get a good stretch of the legs, and inspect the gardens. They entered a blue and white building and congregated in a smallish room with the same blue and white design as the walls outside. All around them were a number of sizeable black and white photographs with long descriptions in a number of languages that confused Gitte.

“Willy, come here and read this to me,” she commanded.

Gamely, Willy came to his sister’s aid, searching out the German texts among those written in different languages that accompanied the old, fuzzy photographs before them. These were pictures of devastation and famine, of what looked to be the same building they were standing in now. Displayed were also old blueprints of the building from which the workers began to laboriously rebuild it back to the way it looked before.

“The story of how this palace was painstakingly rebuilt is a story of the Russian people’s strength and will,” Natasha Petrova slowly narrated. Her voice echoed through the halls and the high ceilings as she tried to speak above the ghostly layers of voices coming in from various parts of the building. “One would never think this to be the same building as you see there in that picture. In the Second World War where nearly twelve million Russians were killed by the Germans . . .”

“Twelve million?” Herr Schlink overheard his granddaughter gasp out. He saw how some of the wives in the tour group turned to look at the girl, holding her in their gaze for a full second with a look of derision.

“Is that true, Opa? Why so many?” Willy tugged at his sleeve.

Bruno didn’t say anything, just chewed the inside of his cheek. He watched the backs of the men stiffen at the question that seemed now to crawl the walls.

“Oh, those poor people!” Gitte said.

“After the Second World War, no one thought that the Katharinenpalast could ever be resurrected to its old glory after the Germans plundered and destroyed it . . .”

Bruno Schlink was indignant. How could this woman, who wasn’t even yet born at the time, who knew what she knew only through schoolbooks, only through black and white history on black and white pages, who knew nothing about what devastation could really do, stand there and be so ignorant? How could she speak of Germans and not know that she was speaking to Germans? Bruno Schlink was indignant.

“But, but, see here, young lady,” Bruno’s voice sputtered at first and then gained momentum, flying over the heads of the people who were standing in front of him to confront her. “What do you know of anything? May I remind you—”

Eva interceded. Eva whispered to him, “Bruno, what are you doing? Stop it, do you hear me? Stop it this instant.”

He did not feel his wife tugging at his sleeve with such urgency that he was practically leaning to one side. Bruno yanked his arm away from Eva and looked at her with such cold disparagement, as if she were the most hated being on earth at that moment. He did not see Eva’s reddening face or see her eyes looking bloodshot with tears from the shock of such a look. He did not see Natasha Petrova’s surprised face as he took her to task, crying “We too, we too suffered!” or for that matter Willy’s own that was filled with fear and uncertainty. Bruno Schlink did not sense the other Germans around him shrink away like mimosas or sense their growing resentment of him for getting them involved in this way. But Bruno Schlink was indignant, and he left the room for everyone to see that.

Hours later, they returned to their hotel rooms, energies spent and exhausted. Even the children were ragged. At the Katharinenpalast, where he hoped the ugly incident would remain, Gitte had cried. Eva herded the two children then and told them that they could run around the gardens for a bit. When they ran away, Bruno watched Eva, still looking to see where they headed. He sensed by the way that she stood, heels to the ground and hand unconsciously clenched to a fist as if she were summoning all of her will to stay where she was, that she wanted to run away with the children too.

No one met his gaze as he entered the bus. As they kept their faces forward or looked out the window, Herr Schlink thought that they were all doing it for no other reason than to punish him. He felt badly about what had happened and wanted his wife to see that. If only she would look at him. On the ride back to their hotel, she still sat next to him—ever the proper, dutiful wife that Eva Schlink was—back straight, eyes forward, with one foot outside the perimeter of the seat to balance herself and her hand clutching the seat in front of them so tightly that he could count the smooth bones beneath her skin. She was occupying only a third of the seat they were sharing; the other third, which was the space between them, was filled by the cold wall of her wish not to have known him.

Eva had left Willy and Gitte with Bruno, who didn’t protest this. They were asleep in the room that the old man and his grandson shared. Willy, in his bed, little Gitte where Bruno slept. There were shiny, sticky traces of sugar and cream at the corners of their mouths from the ice creams that Bruno had given Willy money to buy. It would be another two hours before they were to venture out again for that boat ride on the Neva. Bruno Schlink took advantage of this quiet to look over the painted postcards that he had bought earlier on from one of the young artists selling his work at the market near the art academy. Ten cards. These were little paintings in watercolor of various places in Sankt Petersburg that they had already seen in person. It only cost him ten Deutsch marks. He flipped through the cards, one by one, running his finger lightly over the surfaces where color and paper met. Not bad, he thought, he has a fine, steady hand.

Bruno had been an artist of sorts himself. That was way back when he was a boy, too frail and sickly-looking to ever work in his father’s butcher shop or even to run deliveries to the finer houses of the neighborhood as his father had instructed his older brother to do. Taking meat from such a boy didn’t necessarily instill confidence in well-paying customers, Bruno’s father explained, and Bruno understood. He didn’t much care for his father’s business anyway. Cleaning entrails for sausages. Having bits of bone chip across one’s face. Coming home with collars bloody and hands greased thick with fat. No, these were not attractive things to him at all. But early in the mornings, before the store opened, Bruno Schlink’s father had allowed him to write the prices on the shop’s windows with soap. On certain special occasions, like religious holidays, his father even allowed him to draw pictures on the windows that depicted scenes from the Bible. It would make for good advertising, his father said. It would make people think, “Aha, that is a good German Christian store run by good German Christians. Good meat. Good, clean values. No funny business there.”

A wonderful time, Herr Schlink now recalled. There were nights when he couldn’t even sleep, so excited he was about drawing the pictures in his head onto the glass. He had even saved his father’s shop when the brown shirts came through town looking for trouble. Then one day his father told him, “Write this.” Bruno Schlink still flinched from the memory of his own hand writing those awful words. He had been more concerned then about the words looking straight and bold, more concerned that they look aesthetically pleasing, and less so about the actual harm those words could inflict.

He didn’t realize that he had let the postcards fall to the floor as his hands withdrew to fists, nails digging into his palms, teeth into his lip as if to draw blood. That awful child—we’re not the same person, Herr Schlink consoled himself.

Gitte was beginning to stir. Half dreaming and half awake, she was still whispering out “those poor people!” and sounded as if she would weep again. Herr Schlink went to his granddaughter’s side and shook her gently awake.

“Now, now, Gitte. That’s all over now.”

Fully awake, Gitte asked for Eva, to which Herr Schlink replied, “Why don’t you go and see her now? Let her know you’re all right.”

Gitte hopped out of bed, her clothes wrinkled, her hair so matted that it looked like a bird’s nest. She walked out of the room in her socks. Bruno tidied up his bed and turned to shake Willy awake.

“Come on, Willy, wake up now. You’ll have the rest of the night to do that.”

Willy stretched out of sleep. Then he got out of bed and dutifully followed his grandfather’s instructions to go wash his face. The postcards were still on the floor. Herr Schlink spied them and frowned, not wanting to go through the memory again of how they ended there. He walked a few paces and was about to bend down to pick them up when he saw Gitte standing in the doorway, generous tears rolling down her blotchy red cheeks.

“What’s the matter now, you silly girl,” Herr Schlink smiled at her.

But she couldn’t speak, the unevenness of her breathing getting in the way of her words. Instead Gitte pointed in the direction of the room she shared with Eva. Herr Schlink rushed past his granddaughter to his wife, whom he expected to find dead on the floor. He found the door open and discovered Eva, kneeling on the floor as if she were praying, except that her hands were to her temples. She was rocking herself on her knees that were reddening under her weight.

“Eva, what’s wrong? Whatever is the matter with you?”

She yelped like a little dog, shrinking away from his hands that reached out to her. The old man knew that his wife couldn’t hear him past her own whispering. She was worrying her hands white and pink. Herr Schlink pleaded with his wife to calm herself.

“For the sake of the children, Eva, please!”

Willy and Gitte were now standing, staring at their grandparents helplessly by the door.

“Ah, Rudi! Will you ever forgive us for what we’ve done?”

Bruno Schlink’s hands turned cold at the mention of his brother’s name and he drew back from his wife.

They boarded the white boat that was now cruising slowly over the choppy waters of the Neva. There were others that had joined them on this trip to watch the sunset. Lovers. Other families. Surely other tour groups, too, like the Norwegian businessmen, some of whom Herr Schlink had seen milling around in the lobby of their hotel. With him were Willy and Gitte, both of whom he was trying to distract from thinking about Eva, who was by now in bed and resting in her hotel room with the help of a sedative. He teased them to make them laugh or pointed out the costumes of the folk singers who had come on board to entertain them or tried to get them excited by pointing out how much lower the sun was over the waters. Gitte cooed at the pretty colors the sky was turning.

“I wish Oma wasn’t so tired and were here to see this, don’t you?”

“Don’t worry, she will,” Willy said and looked at Bruno. “We can come back again tomorrow and bring her with us, can’t we, Opa?”

Bruno Schlink duly noted his grandson’s sense of responsibility, of continuing the trail of their conversations, which they were trying so hard to keep light and up. It was as if the three of them were playing that game of keeping a balloon in the air by pushing it up lightly with their palms. Herr Schlink watched as his grandson entertained his sister. Then his mind drifted to thoughts about his brother again. Rudi. Neither his son nor his grandchildren had ever seen his brother, though they knew of him. He had never made a secret of Rudi, talking about him as one talked about great men. “You would have liked your Uncle Rudi the way he was then, Willy. Before the war, I mean. He was a very big man. Full of life. But so kind, which was why your grandmother liked him very much too,” he had told the boy many times.

“And he was not the same after the war anymore, right, Opa?”

“Yes, you’re right. He was never the same Rudi when he came back. But I still loved him. As a person should his family, in spite of what you think they may have done,” he said without hesitating.

“And you did what you thought was best and married Oma so you could take care of her for him, yes?”

“Yes, that’s right. I made a promise to my brother, as you know.”

Bruno Schlink’s family knew of these things. About Rudi. About how Rudi and Eva used to be married. About their daughter who had died when she was so very young in the war.

Bruno Schlink had made a promise to his older brother that night as they stood under the moon, smoking cigarettes. Their mother would have killed them had she caught them, but Rudi only shrugged his shoulders.

“In times like these, who’s to say what’s a man and what’s a boy anymore,” Rudi said, handing Bruno a cigarette and lighting it for him.

It was his first cigarette, and he was surprised at how good he was at it, didn’t cough or choke once.

“See what I mean? Who’s to say?” his brother nodded approvingly. His hand was shaking, making the lit end of his own cigarette dance around like a firebug in the cooling night.

They talked about all sorts of things, particularly the things that Bruno always wanted to know like what it was like to kiss a girl or touch a girl’s breast. He thought his brother a bon vivant of sorts who had seen and done everything. He wanted to know—did their father really finally put funny vinegar in the sausages to spite Herr Kramsch who had long accused him of doing it? Did Rudi really see Frau Bammer, who always smelled like spring cherries, in nothing but a shift whenever he made his deliveries? Rudi answered all of them without hesitancy. “Is that all you want to know?” his brother asked him.

No, Bruno wanted to know more. He wanted to know much more. Everything. And now that he had been given this golden opportunity to get his answers, the questions rushed so furiously together in Bruno’s head that he became tongue-tied and was at a loss for words.

“Fine,” Rudi said, “let me ask you something. If I ask you, will you do it?”

“I’ll do it. Whatever you say,” Bruno answered back.

He had expected for Rudi to ask him to be good or to take care of the deliveries in his absence. Maybe he was going to ask him to take care of the more defenseless children in their neighborhood and take on the job of protecting them in his absence. But it was the last thing on his mind that Rudi should ask him to look out for Eva and especially their small daughter, whom he adored more than anything.

“Will you do that?” Rudi asked him.

“Yes, of course,” Bruno said, surprised at himself.

“I need to know that they’ll be all right. You know, in case I don’t come back,” he said.

“But you will come back, Rudi,” Bruno insisted, “You’re strong. You know everything. You’ll come back the big hero. Don’t you know that?”

Rudi looked at him quizzically, “No, I don’t know that.”

He was bewildered by his older brother’s answer and wanted to ask whether he wanted to leave at all. But instead what came out of his mouth was, “I don’t want you to leave, Rudi.”

In turn, as if it were a secret, as if saying it was the worst sin ever that he could commit, Rudi whispered back, “I don’t want to leave either.” Then his brother shrugged, carelessly, as if the entire situation couldn’t be helped.

The last thing he heard from Rudi that night was, “I wonder what these stars look like from a different place?”

He would never ask Bruno again about Eva and their child. He didn’t look him in the eye to remind him about the promise Bruno had made as he was getting ready to leave. He kissed his mother goodbye and Eva too, who was clutching and touching his face. Their father stood by some distance away, looking grim and sucking on his lower lip. The little girl cried and cried. Rudi ignored him, completely in fact, but Bruno knew why. It was as if Rudi wanted to avoid that whole episode, fearing that Bruno might change his mind and take back what he had promised him the night before.

Eva and Rudi’s daughter had died during the war. She couldn’t have been much older than Gitte was now, Bruno thought.

Night finally descended upon the Neva, rendering the waters invisible. The people could now only hear it slapping against the bottom hull of the boat. There came a collective sigh of gratitude for the day finally being over. They silently cruised the river and could see the lights of the city twinkling out to them. As for Bruno Schlink, he was thankful for the darkness.

Willy and Gitte had slept on the bus trip back to their hotel. Bruno Schlink slung his granddaughter over his shoulder and steered his sleepy grandson back to their room. Once there, Willy, with eyes closed, walked the rest of the way to his bed while Bruno laid out his granddaughter on his, lifting her legs so he could ease the sheets down and then cover her. As for Bruno, he wasn’t yet tired. He returned to the chair he had occupied earlier in the afternoon and simply sat there with his hands together.