by DAVID ALBAHARI

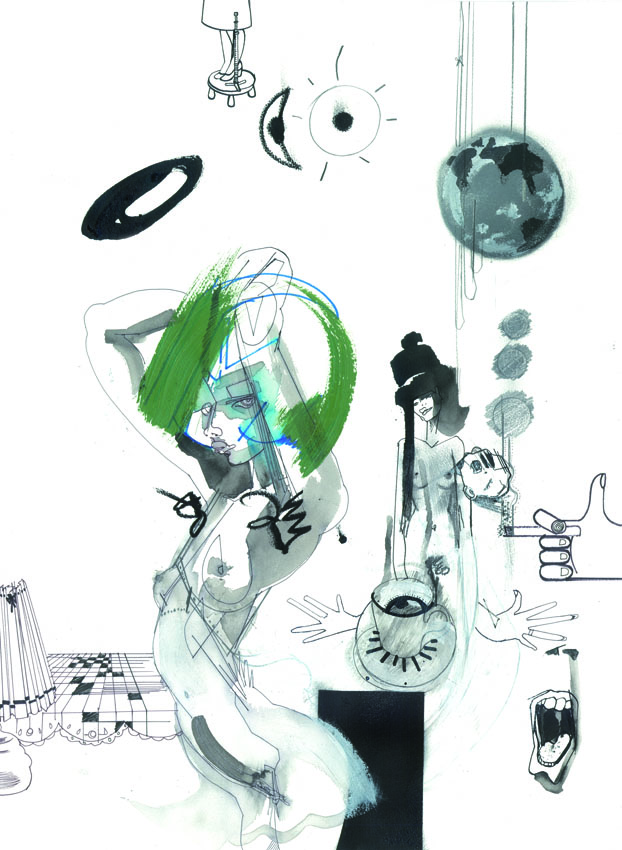

illustrator JULIE VERHOEVEN

ISSUE V

Eli raised his leg and caught sight of Earth. It was smaller than he’d thought it would be, no bigger than a marble, though shinier and more colorful. “Terra,” he whispered, “terra nostra.” Then he looked around cautiously: sometimes a whisper, he knew, carried further than the loudest shout. No one, however, looked as if they had heard him: not the man sitting across from him reading a paperback, nor the woman at the adjacent table who was peering at the screen of her laptop, nor the man at the bar who couldn’t have heard him anyway over the hissing of the espresso machine. His gaze flew over the things which, forming a sort of irregular pattern, stood on the table: two ashtrays, a dish with a moist tea bag, a little spoon amid sugar granules, a cigarette lighter, a crumpled napkin, a kernel of corn and two worn coins. Of course, he thought, everyone will want to know how the kernel got here, though it matters the least of all these things. In fact, it means nothing, because soon a little bird will come for it and eat it.

And sure enough, only a moment later a sparrow landed, looked left-right, approached the kernel of corn and downed it. Then it gave the ashtray a peck, shook its beak and off it flew.

If there was a microphone concealed in the ashtray, thought Eli, the peck of its beak must have reverberated like a cathedral bell in the ears of the people listening in. He imagined them wagging their heads and hastily pulling off their earphones, and he laughed softly.

The man sitting across from him suddenly arched his eyebrows. Laughter, Eli knew, was not held in high regard and he tried to make himself serious, but the more he tried to be serious the more gasping his laughter became, until several policemen burst into the restaurant, surrounded Eli as he was laughing, and in unison raised their billy clubs…

Here I stopped and said nothing until the woman coughed and asked: “So what happened next?”

“I don’t know,” I said and shrugged. “The story stopped here and I can’t seem to take it any further. As if it were lurking in a hole in the wall, deep enough so that I can’t reach it, yet at the same time a hole wide enough that you get a sense of the story’s hem.”

“A story has a hem?” asked the woman, surprised. “That’s the first I’ve heard of it, are you sure you’re not wrong?”

“And not just a hem,” I said with a grin. “A story can have a lining, patches, pleats, and shoulder straps.”

“It’s going to turn out in the end,” said the woman, “that stories are made in tailors’ shops.”

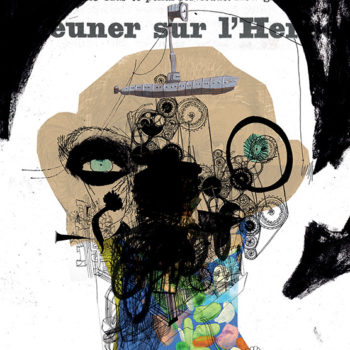

“Precisely!” I exclaimed and several people turned to us. “A writer is a tailor, and a story is sewn like a shirt. And just as a shirt is always assembled of more or less the same parts, so the story is always, essentially, the same. However the details are what make it current, up-to-date, in step with the latest fashion whim. The basic structure of the shirt doesn’t change, it’s only a few of the parts, like the collar and cuffs, a close-fitting or a loose-cut waist, the shape of the pockets and—”

“I get it,” said the woman, “you needn’t enumerate every detail. And besides, I know how to sew. I may not write short stories, but I understand just what you want to say.”

I bent my head so she wouldn’t see the admiration flash across my face. Ever since she and I first met my conviction had been steadily growing that she was the ideal creature for me. But, had I really gotten to know her? I wasn’t sure, just as I wasn’t sure whether the torrent hadn’t simply deposited her at my door or whether we had met on this imaginary bluff, safe for now from sinking and collapse. In any case, I didn’t know her name, where she was from, or how old she was, all of which was confirmation that we had not been formally introduced, yet perhaps together we could accomplish something. For instance: shoot an elephant or rhinoceros while we were on land, and then, when we waded into the ocean, a blue whale would be waiting for us, the largest mammal in the world.

Before that, of course, the apartment needed to be tidied and everything put away where it belonged. I wasn’t sure where I should stow the tea strainer, so I dropped it at random into the third drawer from the top. The tea was somewhere else, up in a cabinet, which I found confusing, this business of separating things that belonged together. If one adds the fact that the pot used to heat water for tea was in the pantry along with all the other metal pots and pans, then my confusion became unbearable.

I scowled and the woman immediately asked whether I had a headache.

“No,” I said, “my head isn’t aching, it’s that I’m feeling uncomfortable about being in a strange apartment.”

“Nonsense,” said the woman, “this apartment isn’t strange, it is my apartment, and we,” she said and smiled, “are hardly strangers.”

I looked at her smile and didn’t know what to do. I raised my leg, but down there, below her, I couldn’t see a thing, not even a worm. I looked at the woman and she patiently waited out my stare. Then she said, “Of course, it all depends on whether all the things you said before you fell asleep on the bench by the promenade last night are true.”

“Before I fell asleep?” I repeated, filled with admiration at her goodness. “It would be more accurate to say: before I lost consciousness from the vast quantity of alcohol.” I remembered that at one point we had left the hotel to take a walk, but from that moment on, all I can see in my mind’s eye is darkness, darkness, and more darkness. I had no idea, for instance, how she’d gotten me to her hotel room and dressed me in a large white T-shirt on which were the words “Don’t ask! Just do it!” I woke up next to her in bed, and she was naked, tangled up in the sheets and with a pillow between her legs. I leaned over and brushed the hair off her forehead. Without the hair her forehead was like a boy’s, so I moved back three or four locks to where they had been, thinking as I did that we should all have our pictures taken so that a database could be put together which would come in handy for all of us.

Afterwards I forgot about the database and it surfaced in my awareness only much later, as so often happens, when I wasn’t thinking about anything. So, suddenly I realized I was staring at a large box, carefully filled with books and I thought of the database and almost burst into tears when a voice said: “Everyone will be in it: Father, Mother, two small children, their toys, your books and shoes, shirts and sweaters, LPs and photographs, and all of it in peerless order, arranged from A to Z, so that it is always extremely simple to find things.”

All of this had dried my tongue which was rolling in my mouth like a log, turning my speech into mumbling, into a series of deceased words, into the sticky story-telling of a person with no teeth.

don’t understand any of that,” said the woman when we’d reached the far end of the promenade, “and it all sounds like a story slapped together in a huge hurry.”

I had no choice, I had to go back and tell it all from the beginning. “While I was walking through the park,” I said, “I caught sight of a woman whom I immediately felt had been created for me, that it was fate that we meet here, in the middle of the park, and that we never part again. I know,” I said, “that these are old-fashioned ideas, hopelessly romantic, but the feeling in me was so powerful that I simply couldn’t breathe.” Without hesitating a moment I went over to the woman, drew her away from her company and told her of the feelings that were welling up inside me and which, as her face grew larger and larger and more precise in my gaze, showed a growing aggressiveness. “Oh, replied the woman,” I said and looked at her, and she went on: “Oh, she said, this is the most thrilling day of my life and of course I want to play my role to the end, I would never pass up such an opportunity.”

I can tell you that a great rock rolled off my heart at that moment. It rolled off and lay between us until I kicked it aside. When I looked up again at the woman, her eyelids fluttered as if she were waking, although clearly she was the most rested and lively of us all. I say this as if there were a lot of us there, but we were only three: the woman, me, and the boy who never leaves my side. The three of us were so tired we were leaning on one another like books on a shelf, which meant that at any minute we might tip over, like books. I have woken many a night when books have toppled over on the crowded bookshelves! And every time I thought I would change the shelves and buy new ones, or, perhaps, spruce up the old ones. I had all the tools handy, all I needed to do was start. The woman coughed gently, warning me not to go on branching the story in countless directions. “Tell about what came later,” she said, “when you grabbed my hand and I said to you: Who are you to be holding me by the hand?”

“Who am I,” I repeated, “to be holding you by the hand?”

“Yes,” said the woman. That she was anxious was visible, that she even feared her own shadow, that she was prepared to shrink so far that no one would ever find her again, but I doubted they would allow any such thing. I sent the boy to arrange for three places by the wood stove and said we’d sleep there, and that they should ready three cots for us. I could, of course, have gone up to the second floor, and entered my childhood room, but I was not in any shape to sustain the flood of nostalgia that would have had me sobbing in bed. “Nothing worse than tears in a bed that creaks,” I said out loud, once we were already under the covers by the wood stove, “because from every sob, every gasping breath, every tear that runs down the face and drips into the ears, the bed creaks all the more, so all that is left is for you to wish you are gone, that everything is at its end.”

“Oh, my boy, my poor boy,” whispered the woman and reached her hand toward my face, but instead of caressing me, she poked her finger in my eye and I howled like a kicked dog.

From all sides came words of protest and open threats, and I whispered into the woman’s ear that it would be better for us to get out and take a little walk, at least until the tempest in the room subsided.

“Yes, of course,” said the woman hastily, “oh, of course. Just let me put on my slip and I’ll be with you.”

She wears a slip, I repeated, elated, while I stood in the chilled vestibule, she wears a slip! I had always been partial to slips and she couldn’t have said anything nicer to me. There was no longer any doubt in my mind that she was created for me, the ideal person no matter how a person looked at her. And I didn’t hesitate to tell her so as soon as I caught sight of her, especially because her slip was showing exactly as much as needed, two centimeters, maybe an inch, something like that. I took her by the hands and told her what I meant to tell her, that she was created for me and that with her I could even venture into my childhood room. “I want to tell you everything,” I said, “every moment of my life, where I was when John F. Kennedy was assassinated, where I was when Tito died, where I was when Slobodan Milo?evi? was arrested, and where I was when man landed on the Moon.”

The woman said she wasn’t sure all of that interested her particularly. She was already carrying so much information as it was, she remarked that her head sometimes dropped from the sheer weight. There is nothing so heavy, she concluded, as information. “After all,” she said and raised an index finger, “how many times has it happened that people die while sitting in front of their television sets, crushed under the weight of news and the vast quantity of information from every corner of human existence. We surely don’t want anything like that to happen to us, do we?”

“Oh, no,” I said.

She looked into my eyes, and said: “But you can tell me a story whenever you please.”

“Really?” I came to life. “Whenever I please? Even now?”

“Absolutely,” she said. “Even now. Especially now.”

“Any story?”

“Any story at all,” she said. A moment later she added, “Except ones with rude language.”

And so I began to tell the story of Eli and his seeing Earth when he’d raise his leg. The Earth was called Terra. Everything else was without a name, as if coming from some new world as yet undiscovered, although that world, judging by Terra, knew full well where it was. The woman listened carefully and from time to time she’d purse her lips, which excited the narrator and influenced the rhythm of the story-telling. Once he even stopped talking altogether, but no one from the audience said anything; post-modernism had taught them they could expect all sorts of things from the new prose and poetry, including interference at a number of levels of content and time. Reality stepped into the imagination and stepped out of it like a knife used for spreading margarine or a honey spoon that isn’t used for anything else.

The woman listened to me with her mouth open. I saw her tongue, I saw her teeth, I saw the dark that led into her throat. Had she been able to swallow me, she certainly would not have hesitated. That is why I had to go on with the story, that is how I defended my life, that is how I stayed alive. But at one point, when I stopped talking for a moment to take a breath, she spoke up before I did and said, “The man from the beginning of your story, what was he afraid of, why was he whispering?”

It took me time to remember what she was referring to. Then I smiled and said I didn’t know. In all of it, I went on, what mattered to me was the sentence about how he raised his leg and caught sight of our Earth. I was entranced by that image and for days I had been wondering where he was, what he was doing, and how he’d caught sight of the Earth at all. I thought the cosmos had been a playground for giants of huge dimensions who tossed planets back and forth the way we toss balls…

“You are lying,” said the woman. “You are lying something awful.”

I looked at her. No one had accused me of lying for ages and I didn’t know how to answer, what to say. And besides, she was right: the beginning of the story wasn’t mine. It was actually a slightly altered beginning of a story from an old anthology of fantasy and science fiction stories. I didn’t know the author’s name, but I knew what his narrator feared: exile on a distant planet (which was described as if it were a Soviet gulag out in space), where mentioning the name of our planet was forbidden. He was afraid he’d be heard by an interloper, and for this violation he would get an additional five years in the frozen gulag.

“That is the truth,” I said to the woman, “you have to believe me!”

“So that means,” the woman said thoughtfully, “that the beginning of the story isn’t yours?”

“Exactly,” I said, “it isn’t mine.”

“So, if the beginning isn’t yours,” she said stubbornly, “then the end needn’t be yours either.”

“Exactly,” I repeated. What with the cold in the gulag, I was ready to admit to anything.

The woman smoothed a wrinkle on her uniform and straightened her cap. She stood in front of me, her legs akimbo. “The end, then, is mine,” she said. “Is it not?”

“So it is,” I said once more, but without looking up. What happened next was up to the woman anyway: a kick, the snap of a whip, a shot from a gun, but nothing like that happened.

“Look at me,” said the woman and when I finally did look up, I saw she was naked. “The next time you go to Terra,” she said, “promise you’ll take me with you.”

“Of course,” I said. The wind suddenly picked up and the woman looked as if she were not walking but flying. I waited for her to reach the gateway to the camp, and then, pulling my cap down over my ears, I hurried after her.

translated from the Serbian by

ELLEN ELIAS-BURSAC