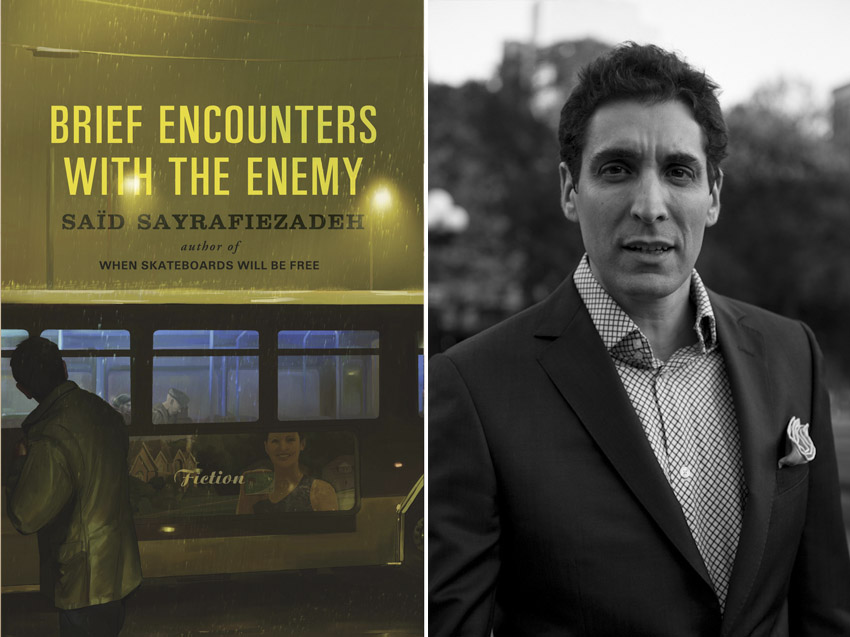

by Brantly Martin

photography Giorgia Valli

25 October 2013

In Brief Encounters With The Enemy, The War is first mentioned on the third page of the first story, “Cartography.” It’s last alluded to, by both the supermarket manager addressing his recently drafted employees, and the handicapped narrator, Max, three pages from the end of the last story, “Victory.” In between, The War colors the stories to varying degrees, like a filter on a camera lens. Did you set out for The War to have any sort of character arc within the book?

I wanted a gradual escalation of war—from rumor to threat to reality. There’s nice drama in that type of build. But if you notice, the war has suddenly ended in the sixth story, Enchantment. Turn the page for the next story and it’s raging again as if it never stopped—with no explanation… I don’t state definitively whether or not this is the same war throughout the collection. I’ll leave that for the reader to decide. What I’m interested in is portraying America against the backdrop of what has been a seemingly relentless, always beginning, never quite ending war for at least the last two decades. That’s been the status quo of this country, and we’ve become so used to it that, like the characters in the book, we’ve stopped questioning it at all.

The symptoms of The War in this book are slow, then fast, and all feel inevitable. A key part of The War Machine—one perhaps unfamiliar to non-Americans and Americans of our generation who grew up wealthy—is the Recruiter. I went to a massive 4,000 person public High-School in Houston. It was straightforward there: a white Recruiter for the white guys, a black Recruiter for the black guys, a Mexican Recruiter for the Mexicans. You slyly drop in this little discussed aspect of The War in “Appetite”: A couple years ago, on the basketball court, an older guy had come over after the game and talked to me about life. He was friendly and showed interest, and I thought he might be gay. He smiled at everything I said. “Is that right, son?” At the end of our conversation, he handed me his business card: Sergeant Robert Alton. “Stop by, son, and talk to me sometime.” I think that about nails it—and in six sentences. But…in this instance are you tempted to give more? To make sure the reader “gets it”?

I’m always tempted to give more, but there’s artistic satisfaction in walking the line between suggestion and explication. There’s a happy medium somewhere between those two. Unfortunately, it’s not always clear where that happy medium is—that’s the challenge. I want the reader to come to some conclusions by themselves, it’s more fulfilling that way for both reader and writer. It means we’re both bringing something to the reading experience, we’re both doing some work, we’re both in a dialogue. The danger, of course, is that what I’m trying to convey might be missed entirely, sometimes—as you point out—by those who haven’t experienced life in a particular urban setting, or in a particular socioeconomic class. They might, for instance, question why my characters choose to join the military rather than going online and finding a new job if they’re unhappy with the one they have. I’m willing to live with that, though.

Back to the subject of the Recruiter. Things have obviously changed in the past 12 – 15 years. There was a window in the 90s where the military sales pitch seemed legit: there isn’t going to be a war, serve a few years, get three square meals a day, a paycheck, school paid for when you’re out and on reserves. It’s a deal that seems to have worked out OK for Jake in “Enchantment”: Everyone thought I was a hero, teachers included, but the reality was I had no choice in the matter, it was the deal I had struck in exchange for my college degree when I’d had the forethought, two weeks out of high school, to go down to the Career Center and sign up. I didn’t want to end up like my mother, working as a telephone operator for thirty years. The recruiter had told me they’d need me one weekend a month unless there was a war. “But there ain’t going to be no war,” he’d said. We both had laughed. What are your thoughts on this deal both in hindsight and its currency today?

That passage is a version of what a recruiter told me over the phone a few months after I graduated from high school. We were ten years past Vietnam and it was hard to argue with him that there wasn’t going to be a war. “That’s not how it is anymore,” he told me when I said I’d just seen the movie Platoon. I was seventeen years old, living at home with my mother, working in a supermarket, not attending college, no idea what I was going to do with my life, and then the phone rings… I knew I wasn’t going to join the military, but part of me wished I could. It seemed like it would be nice to believe in what was being offered by the friendly recruiter. It felt like a comforting place to belong—the military. My character Jake signs up, he makes the choice I didn’t make. He gets his degree by way of the Army and I think he pays a price. That’s one of the pleasures and terrors of writing fiction: imagining what my life might have been like if I had done a few things differently.

In “Victory” the draft begins. Do you think a draft or compulsory military service could happen? There is one school of thought that a draft would be the only thing to piss people off enough to stop the cycle of invasion / intervention. I’m not so sure. I think the money behind the propaganda would be sufficient enough to drown out dissenters as “non-patriotic.”

Anything is possible, sure, including a draft. The reality is that it’s not been necessary. For one thing, the casualties from our recent wars have been relatively minimal. Fifty thousand Americans were killed in the Vietnam War, two hundred thousand were killed in the Second World War, but in nine years of military engagement with Iraq there have been less than five thousand American deaths. If and when the United States takes on a more formidable opponent, as it does in the story Victory, things could change in a hurry.

In “Associates” the stoner dude, Pink, informs the narrator, Nick, that their friend has died in The War when they see each other at the amusement park. He’s somewhat taken aback, but not enough to resist sending a mass email to his, and the deceased’s former, colleagues at Walmart: “I regret to inform…” Who knows how Nick processed this later, but in the immediate he turned to the technology at hand. In “A Brief Encounter With The Enemy” we witness a real time death through the eyes of the soldier. To me, it oddly reads as even more distant than the guy at the amusement park pursuing the girl and receiving news of a friend’s death from his stoner friend. The encounter in A Brief Encounter With The Enemy is most definitely brief, the “enemy” not so clear. Let’s assume one of the enemies is the technology involved in the modern act of killing, something you detail in the story. Would things have turned out differently if the encounter was more personal?

It would have turned out the same for the person being killed: they’d still be dead. But for the person doing the killing there would have been more of a cost. At the very least, they would have had to expend some energy in killing their enemy, unlike merely putting their finger in the vicinity of the trigger. There’s a scene in that same story where drones fly overhead. All the soldiers jump up and down, waving and screaming, not realizing that the planes are drones. Our military has become very adept at doing things from afar. I have a suspicion that the psychic cost is still high.

****

For many reasons, fiction is able to address the various shades and subtleties of racism. You do it hilariously here. Journalism seems to either turn overly academic, PC or holier than thou on the subject. Not sure if you agree?

My characters are occasionally racist, sometimes anti-semitic, certainly xenophobic. I want to force the reader to have to identify with people who, at least in theory, they disagree with. I’m not interested in writing about characters who have the correct politics. I already know all about them. It’s not worth my time to explore good people who do good things, and think the right things—unless I’m just interested in pandering. The point of literature is to take us into someone else’s life and mind. I grew up with people who were racist, homophobic, sexist. Many of them were my friends. I have no choice but to do something with that history—I can’t simply dismiss it. I have to put it to some kind of use.

The pursuit of the girl / woman is a recurring theme in this book and some of your other short stories. It often works out for the pursuer. Sometimes it falls into a grey area of “success.” Juxtaposed onto the pursuit often is the pursuer’s assessment of the male body—both his and those in his vicinity. Sometimes we get a well-placed and strategic wank thrown into the mix. Care to comment on these converging elements?

For starters, I wanted to write love stories. I wanted the reader to yearn for something in the same way that the characters yearn. There’s an elusive ideal of the virile male body in our society that has haunted me much of my life, especially when I was younger. I also never felt very confident or comfortable pursuing women, much of which can certainly be traced back to my mother who was never able to be in a relationship after my father left home when I was nine months old. I had no model, no understanding of male-female dynamics. It seemed secretive and somewhat shameful. But my male characters, happily, feel no compunction in their desire for women, sex and a relationship. They’re open and unembarrassed about it. It took me, however, years to get there.

For a book filled with humor and some happily-ever-after love stories, it can be really depressing at times. The enlisting, The War machine, the cheap American flags from Walmart, the never ending smoke pumping from the factories turning out military parts, the soldier scolding the strikers for being selfish, the going away parties, the parades… It all builds to a hypnotic insanity that portrays a life both pre-determined and absurd. Is there any reason other than random luck that the anorexic waitress isn’t the handicapped supermarket worker isn’t the failed football player isn’t the lonely poetry writing boss isn’t the army recruiter isn’t the acne-ridden kleptomaniac isn’t the undocumented immigrant isn’t the fatherly voice dropping advice isn’t the married woman’s young daughter isn’t the person who takes a bullet over yonder?

I hope it isn’t just random luck… I’d like to think we have a little more control over our lives than that. But you’re right, some of it is probably the luck of the draw. A few things different here and there and we’d all be the predatory poetry writing boss in the story Cartography.

Not always, but often, I think it’s pointless to get into what in a story or novel is based on “something real.” Our memory is all part fiction. That said…you wrote a story for GREY called “Quiet Time.” It begins: There is a man in the public library who looks at internet pornography. Care to elaborate?

I based that entirely on observation: there was indeed a man in the public library who looked at internet pornography. I was enraged by his brazen behavior. I may have also been envious of his lack of inhibition. One day I followed him after he left the library. He seemed like such a pathetic, curious figure that I wanted to know where he went and what he did. He walked for a while, and then stopped outside of an apartment building and made a phone call. Maybe he was hoping to meet a friend. Then he just kept walking. He seemed like he had nowhere to go and nothing to do. What a way to spend a day. But then, who was I to talk? How was I spending my day? I had been following a strange man around all afternoon. In other words, there was some of him inside of me.