Like water, the mind. Quayola and the future of our visual culture.

Text Valentino Catricalà

There is a specific moment in the history of art when human beings started to find a new relationship with nature, to see natural phenomena in an innovative way, to change their perspective on the natural environment. This moment is the nineteenth century, lying in that nuance that fades from Joseph Mallord William Turner to the Impressionists, from innovative artistic techniques to new perspectives that still has to be fully investigated. The nineteenth century was marked by the birth of the first technological devices such as photography and cinema, which increasingly took on the mechanical reproduction of the reality as a characteristic feature of their work. Moreover, in the nineteenth century the world experienced the dawn of the industrial revolution, the mechanisation and the natural exploitation of resources. It is between these poles that a new visual culture was born, and it is between their interstices that Storms – Quayola’s latest work – stands.

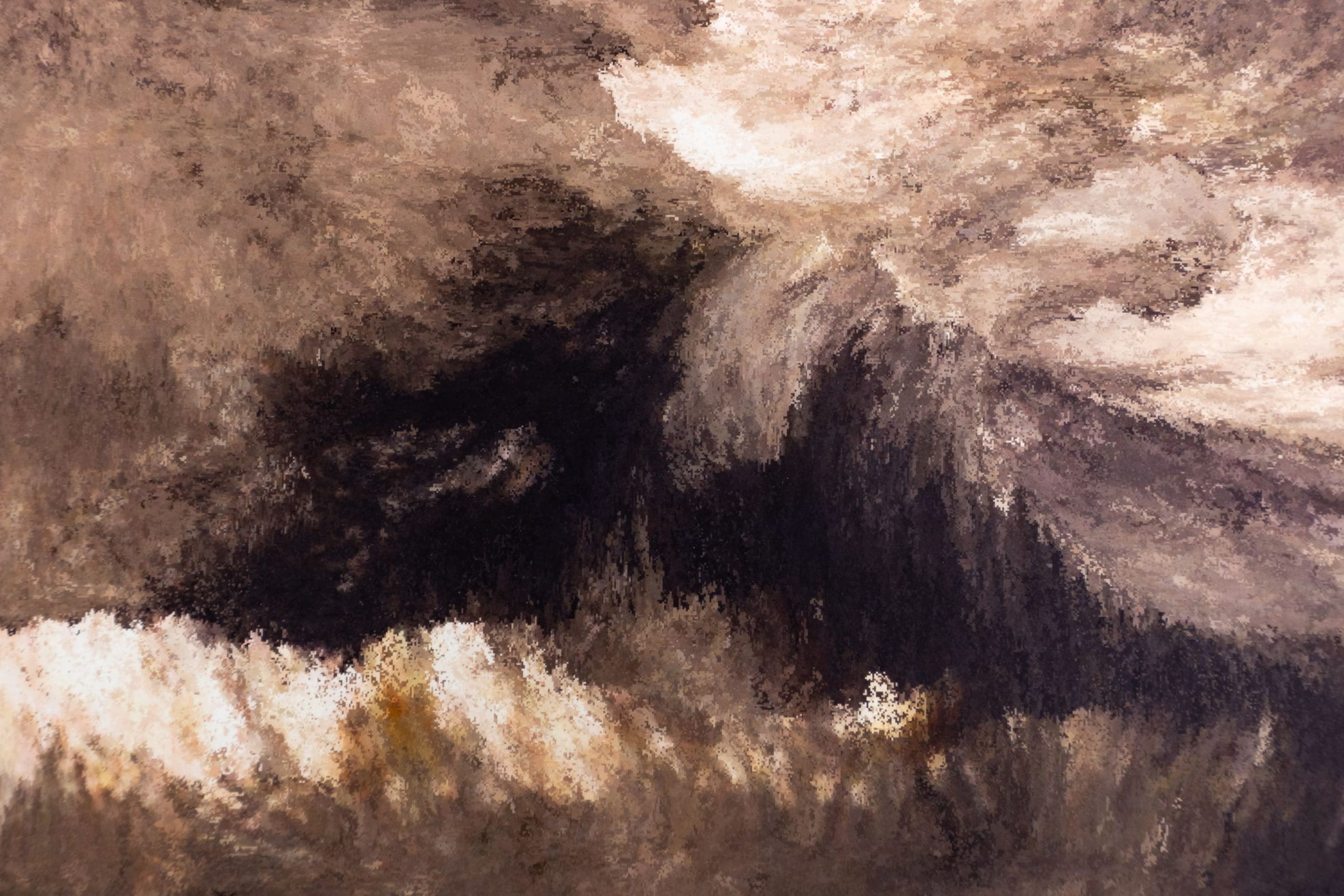

It is well known that Quayola’s characteristic feature is that of a glance at the past, of a digital reinterpretation of the cultural heritage, bringing it back as an interpretative force of the present. This has been one of the artist’s distinctive attributes from the very beginning, marking not only his cycles on the Renaissance and the Baroque, but also his cycles on nature inspired by the Impressionists. A peculiar characteristic that also distinguishes the cycle Storms, his latest work presented at Marignana Arte Gallery: a series of works made up of moving images of storms, very high-resolution videos shot on the same Cornish coast which, not by chance, was also a place of inspiration for Turner.

Exactly like Turner, Quayola’s work begins with the body, with the physicality of the artist. Quayola went to the location in person, exploring, waiting for the right moments and then filming. Quayola took inspiration from the natural context and then shot videos that would be used as the primary material to realize digital paintings. As always happens in Quayola’s work, the filming, the ‘real-life’ part, does not represent the artwork itself but only the moment of data collection which, once captured, are re-processed with algorithmic techniques methods. Thus, what we see are digital paintings in motion at very high definition, in continuous formation, not far from the en plein air technique of the Impressionists. It is the image that paints itself with its own movement: a technique already used in Quayola’s PleasentPlaces.

Water seems to be the protagonist of Storms. However, more than water itself, the fundamental element is its oceanic force, its movement, its sound. It is not a chance that the word Storm comes from the German sturmaz, which hides within it terms such as violence, disturbance, tumult. All these terms are very close to the concept of storm, but they are also linked to a state of mind, an existential condition, an expressive act.

In this case, very high definition is essential and not just a technical mannerism. For Quayola, high definition is a pivotal point as it allows a greater level of involvement with the artwork: an open window on the museum wall in which the viewers can lose themselves. This is exactly the feeling we have while watching Storms: the heavy sound, the white mingling with the blue of the sea, the pictorial sense of the work, spurs a level of involvement which is very close to a meditative approach.

Nowadays, at a time of criticism of the Anthropocene, of a political and critical attitude against the exploitation of natural resources, of which Venice is a symbol, Quayola seems to be pushing this reflection further. Therefore, the fascination with nature, typical of painters such as Turner, is reproposed in a technological, machinic key. It is the gaze of the machine that allows the viewers to rediscover that meditative attitude, to re-enter the lost fascination of nature, of what has been repressed. In Quayola’s work the storm becomes the symbol of that propulsive force, irreducible to any rationalisation.

It is not a matter of looking, but of contemplating, of being attracted. In this perspective, attraction is a form of involvement that captures the totality of our senses, enveloping, seducing and erasing them. In physics, attraction is in fact a force that tends to bring one body closer to another, like gravity. Attraction is a momentary loss of one’s motor and rational skills in favour of their future growth. In an age of technological development, of speed and acceleration, in which humanity questions whether our future will be dominated by machines, cyborgs or technological prostheses, Quayola makes us pause for a moment by reversing technological excess into its opposite. Like a contemporary Turner, he invents new techniques,

new images, to reflect, once again, on the future of our visual culture.

Photo courtesy Enrico Fiorese

Marignana Arte

Rio Terà dei Catecumeni

30123 Venice, Italy

+39 041 5227360

info@marignanaarte.it

www.marignanaarte.it