photography MARCO MICHIELETTO

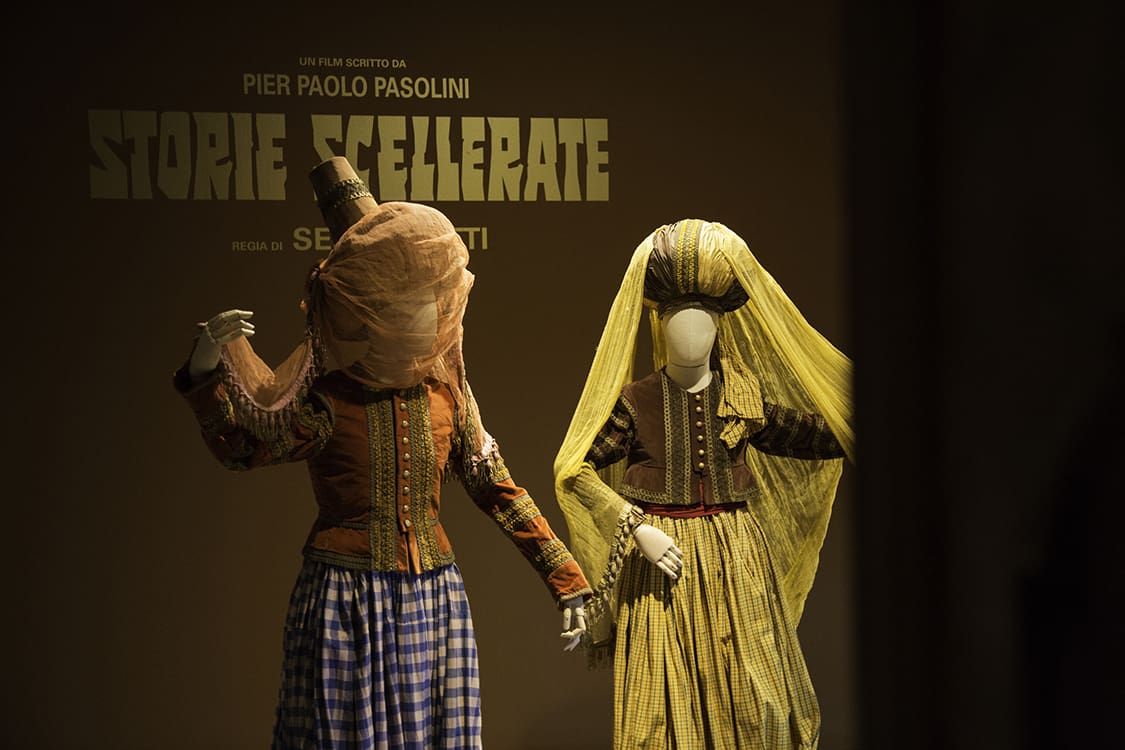

The magnificent site of Villa Manin–close to Udine–has been the frame for the exhibition “Trame di Cinema. Danilo Donati e la Sartoria Farani” dedicated to one of the Italian masters of costume design.

Donati’s relationship with Piero Farani–owner of one of the main tailoring ateliers in Rome–started in the post-war scenary, which showed the rising of Italian cinema in the international scene with the masterpieces of directors such as Federico Fellini, Luchino Visconti, Pier Paolo Pasolini and Franco Zeffirelli–for whose movies Donati created unforgettable costumes.

“This exhibition re-examine Danilo Donati and Piero Farani collaboration with visionary poet/directors and their capacity to produce work with a timeless quality, precisely because it was conceived from the beginning as art. The materialization of ideas took place in words, in drawings, and in a costumier that seemed more like a Renaissance bottega, where they experimented out of instinct and not out of duty.

Donati was a master costume designer, equal to the challenge of creating epics of a timeless future thanks to his ability to project himself into the realms imagined by the filmmaker. He was not restricted by classical scholarship nor by the need to be faithful to an era; on the contrary, he was faithful to an idea.

His relationship with Piero Farani is proof of the benefit derived from the synergy of conception and realization, design and production, artist and artisan. Donati and Farani’s partnership began in Rome in a period when cultural life had just begun to flow again in a society devastated by war. This was also the period when Italian cinema reached world prominence, conveying an image of Italy on the rise yet still struggling to establish itself internationally because, in the end, its success was based on flair and not on method.

In fact, the international system was late in recognizing the value of manual work. Indeed, actors received rewards years before the artisans behind the films; only in the 40s was the first Oscar awarded for Best Costume Design. In the 60s, Italy appeared among the candidates in the person of Piero Gherardi, thanks to the irresistible appeal of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and Eight and a Half. Not surprisingly, it took time for the anarchic, creative style typical of Italy to win over the professionalism of the costume designers in the major studios who had invented Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich and Liz Taylor, fashioning actresses as dolls.

If truth be told, Donati never thought very highly of the Oscars, not even when he won them with Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet in 1969 and Federico Fellini’sCasanova in 1976. This could be due to a competing designer, the American Irene Sharaff, who won in 1967 with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, beating out The Gospel According to Matthew, Donati’s masterpiece that launched his artistic collaboration with Pier Paolo Pasolini.

Beyond that, their entire approach to making costumes was different; Italian art and craftsmanship produced something quite unlike the image dictated by the star system, based instead on a poetic relationship between the director and the costume designer. Rather than imposing rules, the production wisely encouraged a creative vision of the film. Collaborations were born out of elective affinities, out of hours spent in the bars of Rome when the city was still poor but bursting with the creative enthusiasm of the post-war period that generated scores of masterpieces in literature, cinema and the visual arts.

Danilo Donati is one of the most representative artists of the great Italian vitality of that period, of those who built a distinctive new world that is still universally praised, of artists who converged on Rome from all over Italy, forging their way among countless lines of work, sharing rooms and meal and the insight and intuition that outshines university degrees. Cinema, theatre and representation provided opportunities to work, of course, but more importantly, they provided opportunities to put into practice the creative eclecticism that seems to be written into the Italian DNA. With true visionary spirit, these brilliant men and women laid the foundations of a no-limits artisan legacy, one which today–in the context of a crisis not unlike that suffered by their generation–has acquired a renewed appeal and importance.

Donati began working on the costumes and sets for Luchino Visconti, and later, with urbane ease, switched to television where he had the freedom–and penache–to create such costumes as a set of paper outfits for the popular show Canzonissima. This extraordinary artist was capable of generating costumes out of a little glue and a lot of imagination thanks to the skill and flair of Piero Farani, another phenomenon with hands of gold. Between them arose a partnership that kept them working together in Farani’s costumier on pieces that went far beyond mere sartorial products. Each garment was a work of art, each costume a translation of the director’s vision as realized first by an artist and then by an artisan. Without a profound and very personal understanding between all those involved, this creative chain could never have achieved such brilliance–from their impassioned interpretation of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s poetic vision to their creative antipathy for Federico Fellini. Regardless, at all times, they fervently shared a dream using any and all means possible to transcend the limitations of reality.”

— Clara Tosi Pamphili, curator of the exhibition catalogue “Trame di cinema. Danilo Donati e la sartoria Farani costumi dai film.”