Marignana Arte Gallery

Directed by Emanuela Faldati and Matilde Cadenti

Written by Paolo Gambi

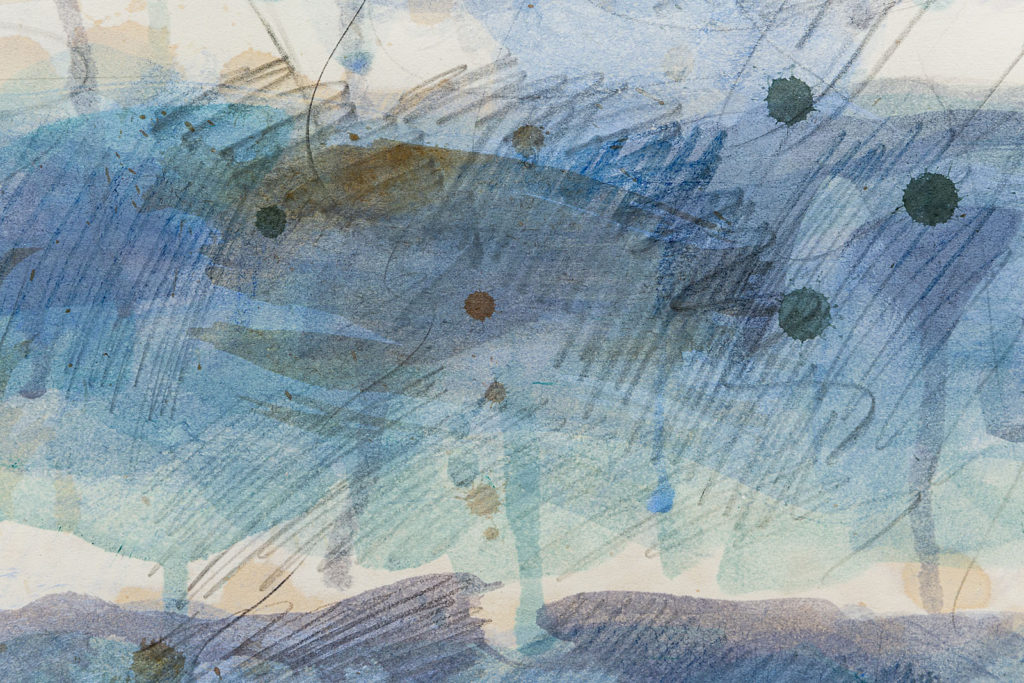

“Ut pictura poesis”, “Poetry is like painting” Horace wrote in his Ars poetica, in the 1st century BC. Poetry and visual art are actually the same thing in a classical artistic conception: the imitation of Beauty with two different instruments. Artists and poets have been aware of this since Antiquity. In fact, at least according to Plutarch’s reports, the Greek poet Simonides (556-468 BC) claimed: “Painting is silent poetry, and poetry is painting with the gift of speech”. Many centuries later, also Leonardo Da Vinci noted in his Treatise on Painting: “Painting is a silent poetry, poetry is a blind painting”. Several months ago I undertook research on the relationship between poetry and visual art together with the venetian gallery Marignana Arte, directed by Emanuela Fadalti and Matilde Cadenti.

This project has seen the light thanks to Domenico De Chirico, the curator of the group show I dreamed a dream (see box), in which each work is accompanied by a few verses I wrote seeking to penetrate the essence of creation and translate it into words. I realized that in the contemporary era the relationship between painting and visual is potentially changeable and that there are at least two dimensions in which the two can intertwine.

Inspiration

Poetry and visual art have always inspired each other. Poets have been writing ekphrases (verbal descriptions of visual works) since Homer’s day: we need only think of the description of Achilles’ shield in book 18 of the Iliad. On the other hand, painters drew inspiration from poems whenever they represented, for instance, a myth narrated by an epic poem. Sometimes the same subject took two distinct interpretative paths: one that led to poetry and the other that transformed it into a visual image. Does poetry guide visual art, or vice versa? Many intellectuals have tried to answer that question. Ugo Foscolo considered poetry as the only creative activity, therefore superior, while visual art was only an imitation process. Others, for example, are Gotthold Ephraim Lessing in the 17th century and Cesare Segre in more recent times. There is no convincing answer beyond all the linguistic or semiotic considerations that have been made. At least, not yet.

Hybridization

Verses and images have however often found a way to meet in a more intimate form. Several intellectuals had in fact been both poets and painters such as Michelangelo and Giorgio De Chirico among many others. Theocritus with his Syringe gave shape to verses, composing both a poem and a visual work, already in the third century BC. Since then, many artists transformed the profound meaning of a poem into a visual work: from Stéphane Mallarmé to Guillaume Apollinaire with his calligrams, not to mention the experiments of Futurism and the visual poetry of Lamberto Pignotti, Ketty La Rocca, or the visionary works of Emilio Isgrò (and all the other artists from all over the world). The poet becomes a painter and the painter becomes a poet. Often painters have even inserted words in their works: an emblematic example for all is René Magritte’s work: Ceci n’est pas une pipe.

Contemporaneity

What we have experienced so far in the West must however come to terms with two factors that could mark a radical change in the relationship between the two arts. The first is globalization. While painting and sculpture have always had the ambition to be universal languages, poetry, due to its linguistic limit, has always been an expression of a certain cultural experience. Even if Goethe theorized a universal literature, no one has ever managed to fully embody all human thoughts and experiences, simply because they cannot be limited to a single language. One of the main challenges that poetry has to face in the present is to understand how to get out of the outdated linguistic boundaries. The second factor is the phantasmagoric technological development. There is a debate that goes back to the time when the Iliad (or perhaps elsewhere the Gilgamesh epic) was put into writing: does poetry has its truest nature in written form or in the oral? Hybridization with new technologies could turn this debate around and resolve it definitively. It is not fortuitously that, for example, a poet like Pier Paolo Pasolini (as Emilio Isgrò pointed out) ended up being a successful movie director. On the other hand, we just have to take a look at the most recent successful experiments – as for example the Videoinsight Foundation in Turin – to discover how the visual art has progressed. Literature instead is still struggling to achieve this awareness.

Perhaps, thanks to this “marriage”, poetry will be able to emerge from the swamp in which it got bogged down for too many decades. Perhaps, thanks to this “marriage”, visual art also will be able to find new meanings.

Chapter 1

30.11.2019 – 07.03.2020

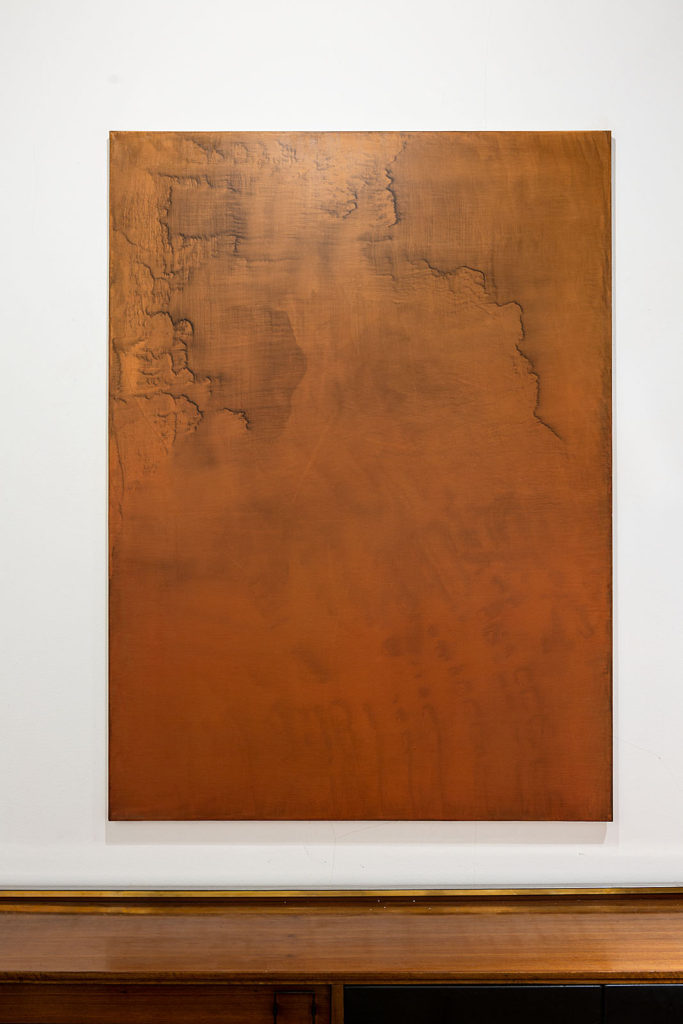

Artists: Giuseppe Adamo, Stijn Ank, Mats Bergquist, Nancy Genn, Sophie Ko, Artur Lescher, Túlio Pinto, Anne Laure Sacriste, Antonio Scaccabarozzi, Verónica Vázquez

I DREAMED A DREAM

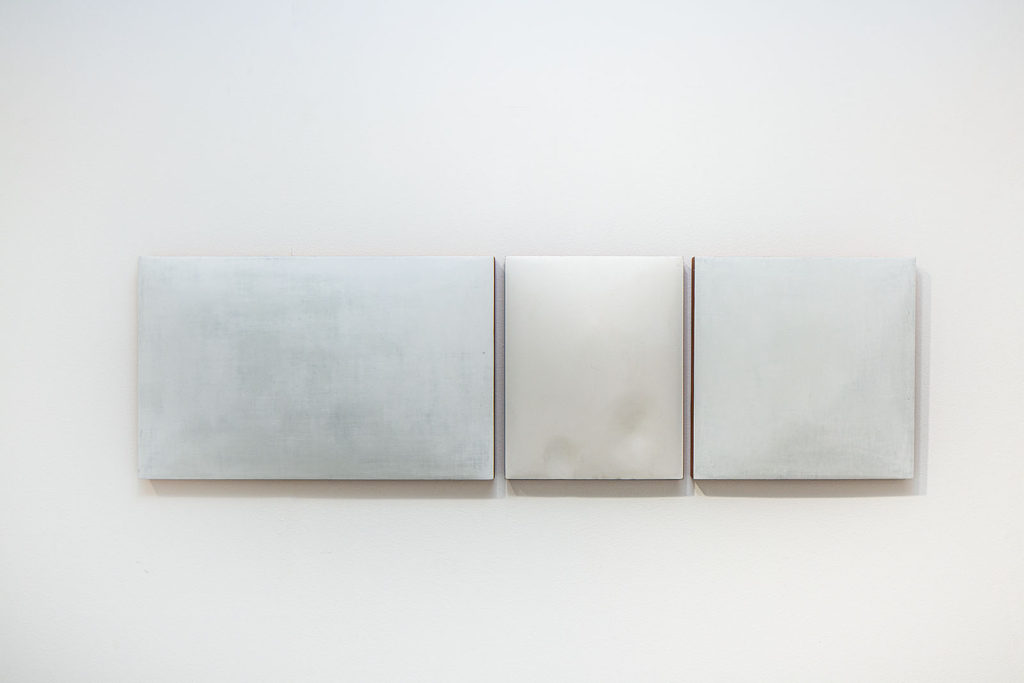

Chapter 2

25.04 – 18.07.2020

Artists: Arthur Duff, Serena Fineschi, Aldo Grazzi, Silvia Infranco, Giulio Malinverni, Maurizio Pellegrin, Quayola, Donatella Spaziani, Marco Maria Zanin.

Curated by Domenico De Chirico

With poems by Paolo Gambi

Translation by Susan Wise