by Claudia Vitarelli

photography Vito Fernicola

coordination Mariaelena Morelli

Under what premise did you open L’Inlassable Galerie? Tell me about the space, and the purpose.

L’Inlassable Galerie was created by accident, if we can say that. In 2011, we decided to co-curate a group show inspired by a legendary French gallerist from the sixties, Iris Clert. The idea was to reconnect with the very free and avant-garde spirit from that era. Reconciling the audience and the contemporary scene was particularly important for us at this point. So the show, Micro Salon, brought together 50 artists working in a small format, and the opening was an extravagant party, starring a micro orchestra playing on micro instruments, and so on … It went so well that we decided we had to set up another show, which led to another … And it’s been more than three years now. We had the chance to move into and open the space in the building’s former horse stables in 2012. It is not at all a white cube but more of a constantly evolving laboratory where “new ideas spring from the shock of two ancient ideas,” to paraphrase Boris Vian. It’s a place where artists, critics, collectors and friends can come to meet and exchange ideas, so it had to be a little bit more welcoming than the average white box. Our wish was to create a place which could both adapt to artists projects and also inspire them. It has to have a strong identity.

Did you set out to represent artists with a similar sensibility or aesthetic?

In a process similar to the one which led to the creation of the gallery, the selection of the artists we are representing is very natural, mostly driven by our tastes and aesthetic. “Retro-futurism” is sometime evoked to describe our editorial line, and we can relate to that as we still feel attracted by traditional mediums—painting, drawing, collage or objects—but we strive to set no boundaries. We have been working with more than 200 artists, of all possible mediums, over the past three years.

Your gallery includes a shop window, which is often an integral part of your shows. How does the relationship to the public at large, passers-by, influence your curatorial choices? Do you value this exchange?

For one year and a half the only space we had was that shop window on the street. Meaning we had to constantly reinvent shows, and come up with challenging curatorial ideas and performances in order to never loose the public’s attention. This is where the name of our gallery comes from, in a way. What’s great about that space is that you directly confront your ideas with the people passing by, most of which may have never attended art performances. Of course we’ve had bad reactions—the window was broken, covered with paint, with graffiti calling us satanists, or even ultra-catholic censorship—but most of the reactions are extremely positive. It is a way for us to keep reality and the audience in mind. You can easily be carried away by the art world’s constant escalation.

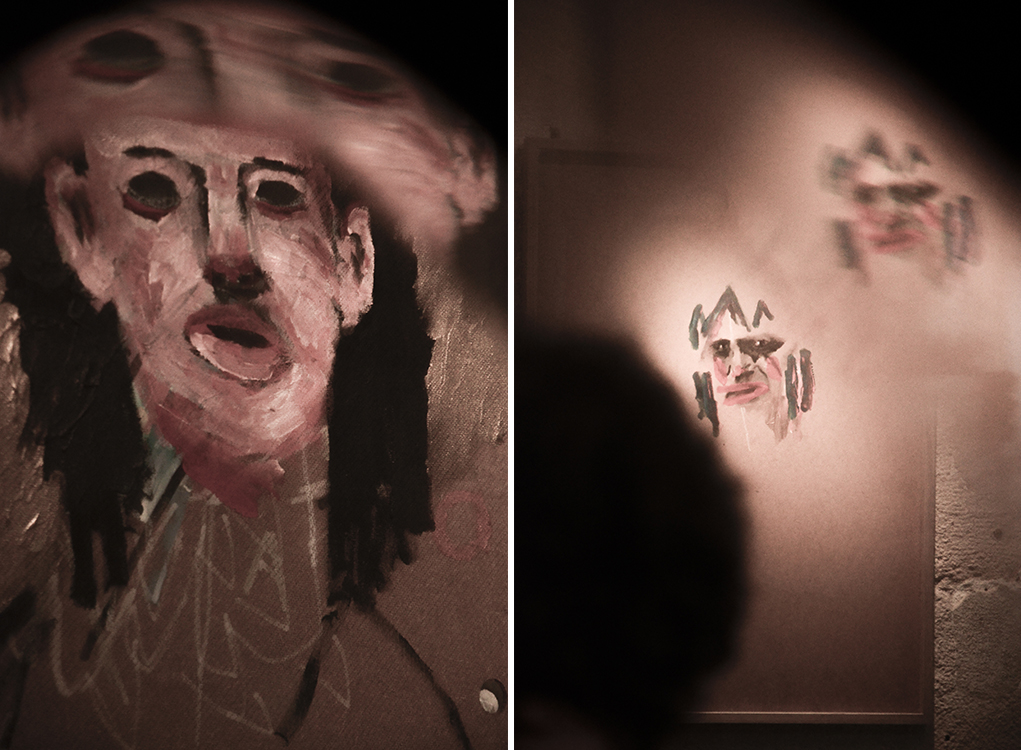

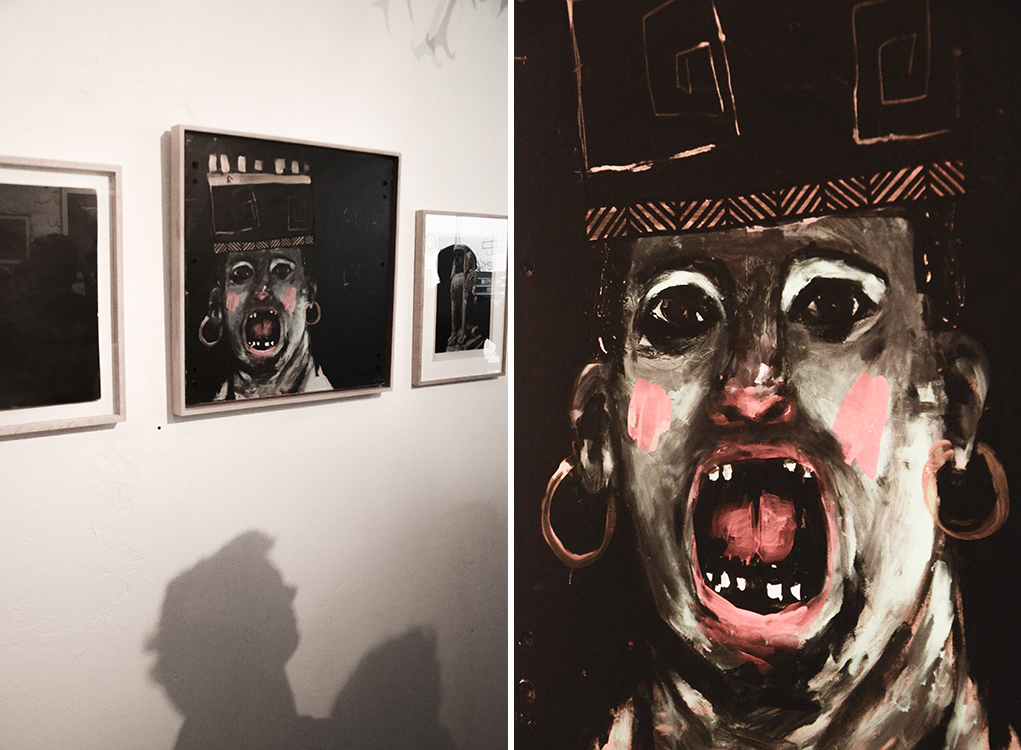

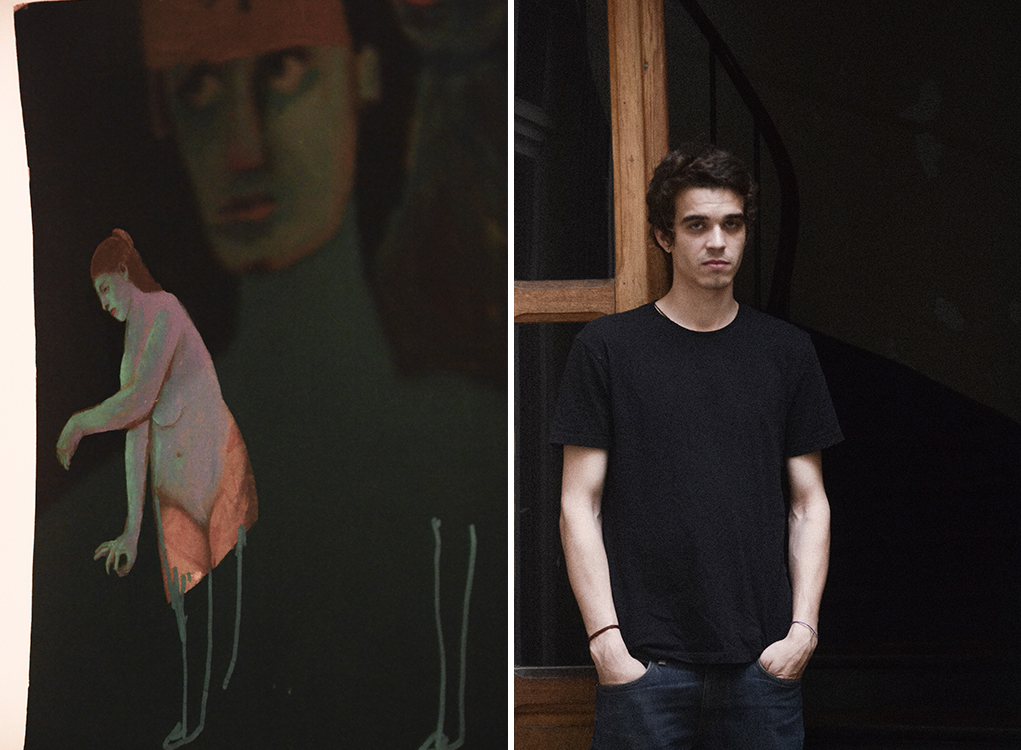

A personal favorite of your recent shows was one of new work by Gaspard Maîtrepierre. How did that selection of work come about?

We presented the second solo show of Gaspard Maîtrepierre, Caeli Patromonium Labitur (The sky’s heritage collapse), which is actually part of an ongoing project started in 2012 with A stellis actum ad stellas. The show is bringing together recent paintings on media as diverse as beer cans, doors, stuffed animals and archaeological book pages, all of which can be seen as clues or keys to the understanding of Gaspard’s personal mythologies.

In presenting Gaspard Maîtrepierre you stress on the fact that he is a self-thought artist. Is there such thing as a “trained artist”? Does the difference even have significance?

The concept of a self-taught artist nowadays makes less sense than in 1945, when Jean Dubuffet first developed interest for what he called Art Brut, the outsider art. At the time, fine art schools and their prominent teachers were still extremely influential. Now of course, contemporary artists come from such different backgrounds that the idea of a training, a unique education path, is absolutely outdated. But we like to see in this recent renewed interest in outsider art—in initiatives of institutions like the Museum of Everything for instance—a response to this cold and stiff post-modern academism who contributed to the rupture between audience and contemporary art started in the late eighties. In following this idea, we wished to emphasize the fact that Gaspard Maîtrepierre’s work is the result of his urge to deliver and share a message which has gone through the sole filter of his individual experimentations. An approach similar to that which had caught Dubuffet’s attention in the ’50s.

Can you expand on the concept of “celestial influences” that Maîtrepierre referenced in the title of the show?

The reference to the “celestial influences” relates to Gaspard’s personal beliefs, and his sources of inspiration. Let’s just say that non-earth civilizations, and their supposed influence on mankind, occupy a significant place in the pantheon he is elaborating.