by Monica Bautista

illustrator Carolina Melis

Issue VIII

“The hills step off into whiteness.

People or stars

Regard me sadly. I disappoint them…”

-Sheep in the Fog, Sylvia Plath

I can’t feel my limbs. I can’t steal a single breath. Everything is spinning into a haze, and I can’t tell dark from light.

I can’t feel my senses.

I. Can’t. Feel. Anything.

All I can think about is this void. For the first time in my life, I am free. In the midst of this nothingness, I am alive.

And then it all sinks in: I am ephemeral.

I breathe once.

It is my last.

It’s hopeless,” I finally say, flipping down the screen of my brother’s laptop. “I’ll never understand any of it.”

Dylan shakes his head, laughing lightly. “Come on, Sylvie,” he reaches for his laptop and flips the screen back to life. “You aren’t even trying. It’s as clear as day.”

“Well, it’s a damn rainy day then.” No matter how many times I tried, I just couldn’t bring myself to appreciate the work of my namesake, Sylvia Plath, or any other poet for that matter.

I just couldn’t sink my teeth into the artistry of it all. Poetry never appealed to me. I mean, how hard was it really to write, “I’m sad because of…” whatever godforsaken reason there was. Surely the best way of expressing it was to be straightforward. Concise. Poetry left too much room for interpretation. And misinterpretation.

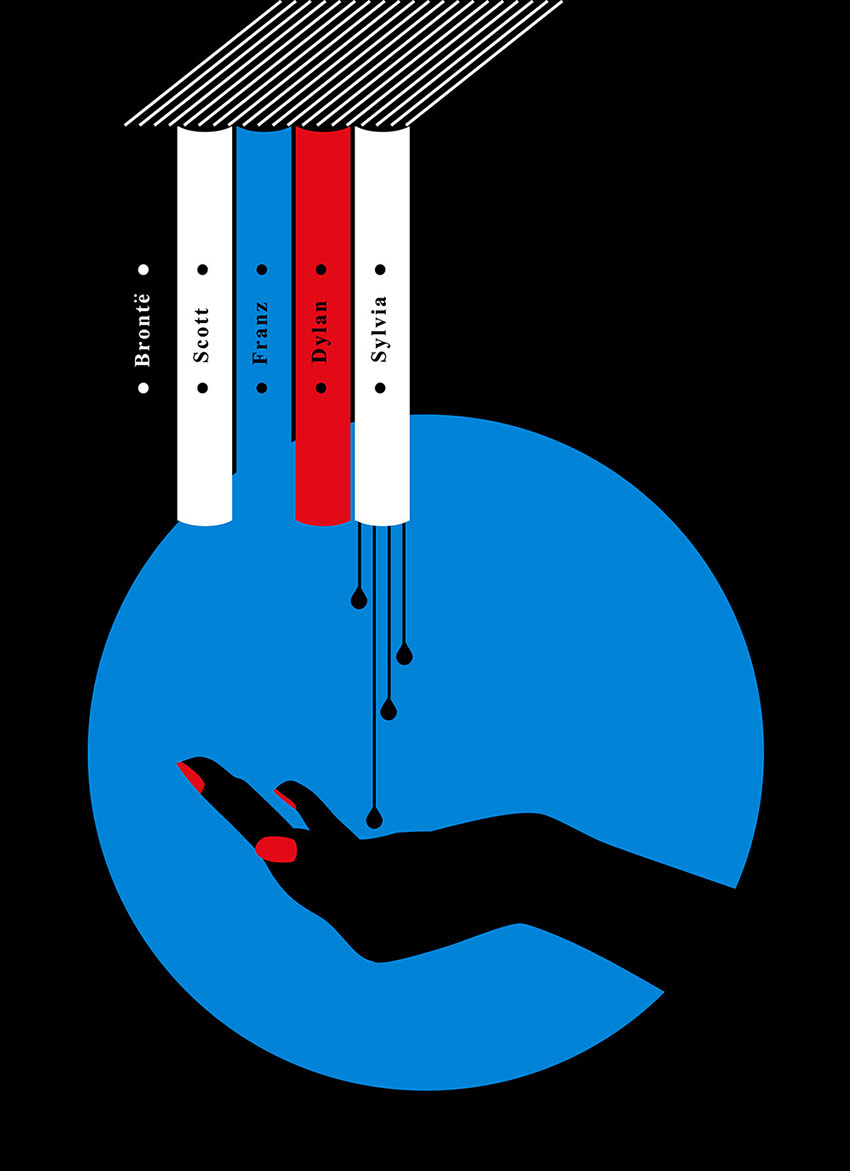

My brother, Dylan, named after the Dylan Thomas, is the complete opposite of me. He embraced the life of his namesake, down to his very alcoholism. Then again, everyone in my family is an alcoholic. Especially my mother. She, the literary aficionada, named all five of her children after writers. Dylan, Brontë, Scott, Franz, and me: Sylvia. They were all involved in the arts, in one manner or another, while I, in my last year in college, majored in Physics and minored in Astronomy.

“Come on,” Dylan prods me, grinning like a half-baked idiot. “Try again.”

I lean back and roll my eyes. “No. Don’t wanna, not gonna.”

“Okay.” He gives in, but the way he says it sounds more like, “It’s your funeral.”

Mother wants to discuss our namesakes over dinner. It is the first time all five of her children would be home in about two years. Growing up, we had a tradition of having a subject at dinner every single night. Being the youngest, I was never really able to catch up with most of it.

We talked about everything from neoclassicism to capitalism, down to alternate and parallel universe theories. Come to think of it, it was the latter that made me interested in physics. There was—is—this idea in my head that it could be real, and I wanted to be the one to prove it.

Big dream, I know.

“Besides,” I continue, “among the four of you talking about your namesakes, I’m sure Mother wouldn’t even notice my participation.”

“Or lack thereof,” Dylan drawls.

“Whatever.”

Dad pokes his head inside Dylan’s bedroom door. “You mother’s fixing drinks downstairs if you kids want to join in.”

I shake my head, “No thanks, Dad. Dylan’s trying to prep me for dinner.”

But my brother is already halfway out the bedroom. “You’re on your own, Sylvia Plath.”

****

I watch sullenly as he packs his bags, silently cursing the name I had been given all those years ago. No matter how far my life is from Sylvia Plath’s, do I really have to be cursed by my namesake’s fate?

I watch as he breathes heavily, moves slowly. My own Ted Hughes. Lying, cheating, son of a bitch.

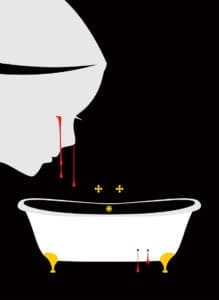

Beautiful. Just beautiful. Now to go stick my head inside an oven.

He stands and looks at me sadly, as if he weren’t the one at fault. “Sylvia—” but I cut him off.

“Go, Nick. Just go.”

He shrugs, shakes his head and walks out of the door. Out of my life.

I pour myself a glass of whiskey and cry.

****

I am home again, and yet everything seems different with both my father and mother gone.

Dylan pours a glass of wine and carefully slides it to my side of the table. “Have a drink, Sylvie.”

I take a sip with wordless thanks. “I’ve been writing.”

“That’s good.”

“Yeah.”

We are silent for what seems like hours.

“It is.”