by Anonymous NYPD officer

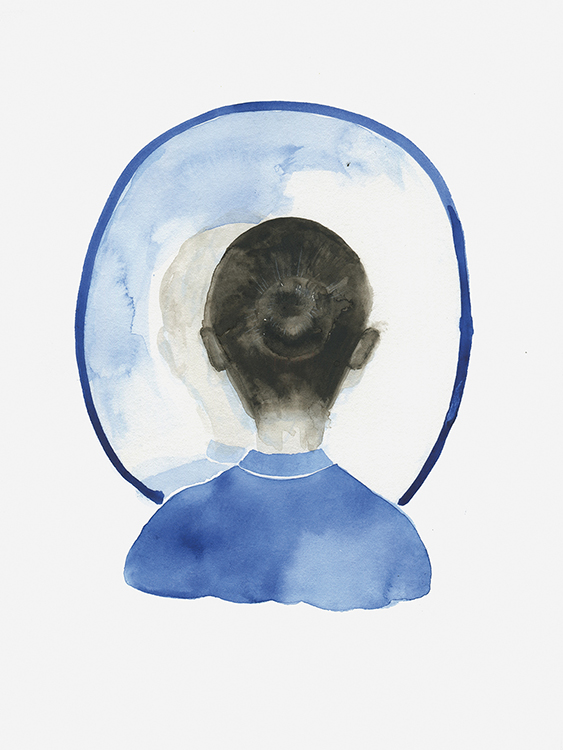

illustrator Anafelle Liu

1.2

Editor’s Note: In keeping with what’s clearly become a habit for the Social Issues section, we give the floor over to an under-heard—and in this case, quite controversial—voice in society: the police officer. This being Grey, hers is no ordinary point of view, and she’s no ordinary cop. Commissioned and written before the recent events of the Eric Garner Grand Jury outcome and the execution of Officers Rafael Ramos and Wenjian Liu, the story is more prescient and relevant than ever. In the name of (and hope for) more transparency within the criminal and justice systems, we present to you one person behind the uniform.

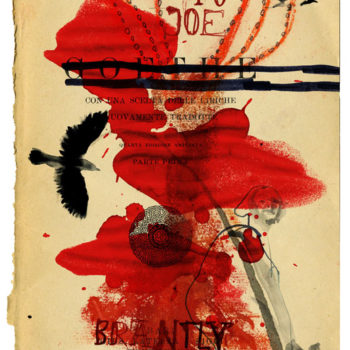

“Wild Women Don’t Get The Blues”

– Ida Cox, Chicago, 1924

My first uniform was a pink leotard and pink tights. Not a black leotard, mind you, the leotard had to be pink. My ballet teacher absolutely insisted; she said pink was de rigueur for little girls at all the grand schools in Europe. Black leotards, she implied, were bourgeois. I had no way of knowing if any of that was true, but I slurped up every word. My teacher walked on water. She wore enormous cashmere pullovers and tied her hair up with gorgeous scarves that made her look, in my romantic imagination, like an impossibly decadent gypsy. She carried a Louis Vuitton bag the size of a small rhinoceros, chain-smoked Capris, and drove a Mercedes diesel. She was the most glamorous woman I had ever met.

Besides, I was a real little snob and I liked the idea of our leotards setting us apart from other, more common children who hadn’t gotten the memo about how things were done on the Continent. I liked knowing that I wore a pink leotard because I went to Conservatory Ballet and, goddammit, that stood for something. All these years later, more than I’d like to admit in mixed company, I still wear a uniform, except this uniform is blue. It stands for something too, though no one, least of all me, can quite agree on what.

Duty Jacket: waist length, navy blue nylon, with zip-out Thinsulate(R) lining, knit wristlets and waistband, and zip side vents.

Shirt: dark blue, military type, polyester/rayon with appropriate service stripes. Authorized shirts will have a label affixed on the inside of the shirt between the fourth and fifth buttons that states: approved nypd, certification # ____.

Duty Trousers: navy blue, polyester and wool, with half-inch braid attached.

Ballistic Vest: Threat Level IIIA or higher.

In proper uniform I am a study in absolute conformity, no modification or personalization is allowed. Everything is specified, from the length of my nails (no more than a quarter-inch from your fingertip, painted in neutral colors only) to the length of my socks (no less than three and no more than five inches above the ankle, black only). My identity fades and I’m transformed into a symbol, a cipher, completely conspicuous yet almost invisible.

I’m walking in Boerum Hill on one of the first really good days of summer. It’s been a long week but I’m feeling good in a flowing sundress and sandals, relieved to be freed from what I’ve begun to think of as my blue polyester prison. I look up and realize with amusement that I’m walking by an actual prison, or, to be precise, a jail: Brooklyn Central Booking.

The doors to the courtroom lobby open and a man emerges, pausing to survey the street. He’s a little scruffy but then the newly arraigned usually are—there aren’t many opportunities to freshen up in the holding cells. He has an open, pleasant face, and the recognition on my part is immediate. My heart sinks as I see him cross the street and make a beeline for me.

“Miss? Miss?” He doesn’t sound particularly confrontational and I give him my best blank smile, hoping he has some kind of mundane procedural question.

“I don’t mean to like bother you or anything, but if you’re not busy, and a beautiful lady such as yourself is probably busy, but if you’re not busy I’d love to buy you a cup of coffee.”

Now I have to grin. This is my new favorite person in the world. What chutzpah! I’m so delighted by this guy that I almost chuck him on the shoulder. Then it hits me. He doesn’t recognize me, at all. He has no idea that I’m the person who arrested him two nights before.

The NYPD uniform is as iconic as it is polarizing. Wearing it makes me a target for both praise and censure—neither of which I, in most cases, did anything to deserve. My character becomes a many-sided die, the cast contingent on the preconceptions and experiences of whoever is looking. With each person I encounter I wonder how it’s going to be: Am I an oaf? A hero? A pawn? A tyrant?

A young man points at me in my recruit uniform as I’m exiting the subway at Union Square. “Oh, look!” he shouts, “a future asshole!”

A well-heeled gentleman sneers as I take his burglary report, “I don’t expect you to be able to appreciate this, but it was a Patek Philippe.”

I’m on a post downtown and a man gets choked up looking at the Word Trade Center site. “I just want to thank you for everything you do, Officer. What you guys did that day, I’ll never forget it.” I don’t have the heart to tell him that in 2001 I was trying to be an actress and competing with my hand-model roommate to see who could be the most self-absorbed.

A protester exhorts me as I block his entrance to the New York Stock Exchange: “You don’t understand! You’re working class! You should be on our side, not protecting these bastards!”

“Look, Brittany, a real lady cop. She’s a genuine hero and I bet if you ask her nicely she’ll let you take her picture.”

The uniform is kinder to men than women. The vest fills men out, broadens their chests. Women are cocooned, squeezed, flattened, we become square and graceless, Lego figures come to life. A homemade poster in my first locker room showed a picture of a particularly short cop. “WANTED,” it read, “For Criminal Impersonation of a Mailbox.” It should make me feel sexless and maybe it would, if female cops weren’t fetishized so often and so blatantly.

“Hey Baby, you can arrest me anytime!”

“You too pretty to be no cop. I got something better for you to do with your mouth than order people around.”

“Those handcuffs give me wicked thoughts!”

“You are one fine piece of pussy, but you’re also a real bitch.”

“Just wait until I get out of here. You won’t feel so superior with my dick in your ass.”

I’ve developed a thick shell, hard and knotty as an old tree, but the level of vitriol can still surprise me. It’s not uncommon to be called a “fucking pig” by a toddler while their goading parents, triumphant, look on; or a “fucking Nazi” while doing nothing more controversial than standing outside of Macy’s during the Christmas rush.

It’s already been the worst tour of my life. A woman on a scooter gets broadsided by an SUV that was speeding up to beat a red light. I’m the first cop on the scene and she dies in my arms. Then my lieutenant, a skidmark of a man, makes me deliver her personal effects to her family because I’m “sympathetic and good at talking and shit” and also because he’s too big of a coward to do it himself. The husband is barely coherent but has obviously told his two small daughters, because one is catatonic and the other was walking in circles, sobbing weakly and murmuring, “I’m sorry I didn’t pick up my toys. I’m so sorry, Mommy. I’ll pick them up every day from now on, I promise.” I hand over my pathetic offering in a battered ziplock bag. I’ve tried to clean everything off but you can still see traces of blood in the ridges of her iPod. Looking into her husband’s eyes reminds me of an Anish Kapoor installation I’d just seen—a rigid structure containing an endless black void—a cacophony of nothingness.

Leaving the grieving family and, feeling like I’ve been soundly beaten with a brick, I run right into a grand larceny auto in progress. A foot chase into a local park ensues and ends with me hauling a short, slight teenager out of a large planter where he was trying to hide. I cuff him and start to walk him to the car. I’m exhausted and overwhelmed and maybe sorta about to cry. We pass a woman with a snotty designer dog, who looks at me with pure loathing. “What are you doing to that poor boy?” she demands, her voice rising to an acidic wail. “You ought to be ashamed of yourself. You all ought to be ashamed of yourselves.”

Sometimes I do feel shame; I can remember folding uniform shirts in a laundromat as a story about a man killed in a particularly egregious police shooting played on the TV news. One that should never have happened, one where we straight-dope fucked up. Everyone in the place was riveted, and just as our union chief came on to deliver his rote, empty, exculpatory platitudes they started to notice me and what I was folding. I felt sure they all hated me and all suspected, in that moment, that they had a right to.

Turmoil hit, emotions so seething and contradictory I could barely even identify them—shame, yes, but also defiance, disgust, horror, pride, love, all piled onto a simple blue shirt with a simple embroidered patch.

Sometimes I feel like a bully, a cheap blowhard enforcing petty rules.

Sometimes I feel like a cog in some obscene apparatus that few people understand and no one can control, a punch-card in theTuring Machine of big money and institutional racism and human misery.

Sometimes I just feel like a bureaucrat—a yellowing, servile bean-counter straight out of something by Gogol, scurrying around a crumbling provincial office having sold his soul for a pension.

But sometimes I feel like what perhaps I really am, a small person in polyester blends doing a maddening, vital, impossible job. One person among thousands of others, many of whom I love and respect, who you might even respect, if you met them.

And sometimes. . . .

I’m absentmindedly walking back to my car from making a traffic court appearance. I can’t stop thinking about my last case, a lady I’d stopped for talking on her cell phone. She was guilty as hell; my testimony was unassailable and her excuse—that her smartphone wallpaper was a picture of her dead mother and she was self-comforting by rubbing her phone on her cheek—was laughable. But there was nothing funny about her parting shot to me after the judge found her guilty. “I hope your mother dies tomorrow so you can see how it feels!”

So I’m thinking about my mother and how I most fervently hope she does not die tomorrow when I’m approached by a girl dressed up as if for a date. She’s in her best Baby Phat knock-offs, trying so hard it almost makes me sad. She can’t walk in her shoes and is carrying her clutch handbag like it’s a precious artifact. She’s also very young and stunningly beautiful.

She asks me if I can help her get back to East New York. She’s jittery, unfocused. She needs to get back right now, she says, she wants to go home. She was with this man, she explains, she met him and he was okay at first and even took her to Applebee’s but then he got really creepy and he didn’t want to let her leave. She managed to slip away while he took a phone call but she’s scared he’s still looking for her.

At that moment a man walks up behind her and put his arms around her waist. There’s something both proprietary and predatory about the gesture. He has a reptilian look, a neck tattoo, and is built like a brick wall. “There you are, girl,” he says, giving her a wet kiss on the shoulder “I was wondering where you’d got to. Come on, now.” He turns to address me: “Don’t worry, Officer, I got this little shorty, it’s all good.”

I draw myself up as much as possible and put on my “this-is-what-is-going-to-happen voice.”

“This young lady wants to go home. Alone.”

“Aw,” he says, “We just had a little argument. It’s nothing to worry about.” He reaches out to grab her arm but I catch his wrist before he can touch her. I look him square in the eye; I know he has a decision to make and I’ve seen the expression on his face a hundred times before. I don’t imagine for a minute that he’s scared of or impressed by me. It’s the uniform he’s thinking about, and what it means, and the several dozen guys that are going to show up if he jumps me and can’t manage to take me out before I can get to my radio.

Decision made, he smiles a tight, revolting smile. “I’ll see you again,” he whispers, and casually walks away.

Sometimes I love my uniform very very much.