by BRANTLY MARTIN

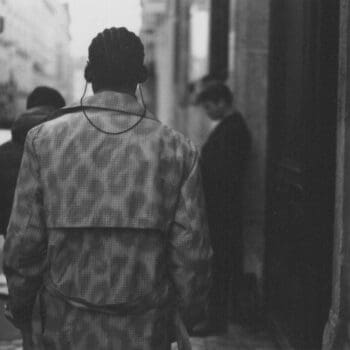

photography ALESSANDRO SIMONETTI

1.1

Eight years ago, in the summer of 2014, I was alone in Rome long enough to slip into fits of grandiosity that might have been madness. This was before the electric shock therapy (administered via abstinence) allowed me to differentiate posterity from posterior. I received an invitation from an Italian photographer friend of mine to meet him in Venice. I’d told myself I was not leaving Rome until a first draft was done. I was there to write a book and that was that. No Italian shenanigans. Focus. Task at hand. All that. But there are different ways to lose the plot and it seemed the non-epistolary iteration was impending and perhaps a change of scenery, along with some basic human interaction in the form of Ciao and Come va? and Bene ragazzo might be called for. My Italian photographer friend told me in Italian-English that he was shooting something he called “___ ____ ____ __ ______.” (I’d known this guy a few years, so I knew he wasn’t a cornball, and I knew that sometimes in Italian-English these phrases were unavoidable.) Were it any other city I never would have made it past Barberini, never would have left Rome, and would have picked the plot on the page over the plot in my head. But Venice is Venice. I’ve been telling myself Vivrò li since 1998. Vedremo amici.

So I chose which plot to prioritize and took the train to Venice. The first night I walked from Dorsoduro to Cannaregio: tramezzino, gelato, Ghetto Nuovo. The second day I met up with the Italian photographer and his American girlfriend and we hopped the vaporetto to Giudecca where we met up with some locals—born and raised Venetians—who’d taken over a storefront along the Canale della Giudecca. (Architects or graphic designers or both.) The following ensued: Four or five of the Venetians walked us to their communal boat. Capitano told me that Venice, the realVenice, had become the Naples of the North—no, the Scampìa of the North. Hai Capito? Yeah dude, I got it.

We piled in the boat. There were seven or eight of us; the boat was made for five, maybe six. Cinquecento rules applied: snug is good. The local that grabbed the wheel was wearing a shirt that said KEEP CALM AND CHE PENSI CAPITAN. (No, really.) His name was Marco or Paolo but I called him Capitano and he asked me if I’d ever seen Venice “like this.” I lied and said no. I always lie and say no when I’m about to see Venice like this. I think it’s better for everyone.

It was around seven PM: sunset, breeze, tutto andava bene. Two of the Venetians on board were a couple. (I have no idea what their names were, let’s call them Roberto and Chiara.) Roberto and Chiara were three sheets to the wind—smashed, bombed, wasted, lit up. (The Italian language never had the need to develop as many words as its English counterpart to accommodate the various states of drunkenness, but, trust me, those two were all of them, and chugging prosecco from the bottle as we untied.)

We made our way through maritime back alleys, down canals both grande and stretto, past Murano or Burano or, maybe, both. (I never pay attention in that waywhen I’m in Venice. I know I know: buy a map Brantly. But I don’t really want to know what’s going on when I’m there for the same reason I don’t want to laser my eyes into perfect sight: when you’re blind you’re not accountable.) Roberto and Chiara began fighting, or at least screaming and gesticulating. The boat began to rock. No one, except me, seemed to notice. It was as if demonstrative arms and flailing hands and tipsy boats were a dialect native to this lagoon and Roberto and Chiara had been tasked with ensuring the tongue’s survival in the face of globalization.

Capitano told me we were headed for the Lazaretto Vecchio—only he called it something else—and asked me if I knew the history. I was too frazzled and overcome by fighting-couple-phobia to play dumb. I, or someone that resembled me, said: Yeah, the plague. The bodies. Capitano said: Yeah, sure. But do you know about the research facility? Me: Research facility? Capitano: For the past ten years or so they’ve been digging up the bodies, the skeletons, the bones. They’re perfecting the antidote. Things don’t move in the old linear fashion these days amico. You should know that. They need to perfect the antidote before they market the new plague, and they need to refine the new plague to make sure there is no cure. The secret to all of that is in those bones left over from the old plague. Me: Who’s they? That’s when Chiara started punching Roberto in the nose. Three jabs and one right cross. The last one, the right cross, translated into any language as: broken nose. All respect for endangered dialects was gone when Roberto, after the initial shock, threw Chiara overboard and told Capitano to “leave her in the lagoon.”

I’m lying. None of that happened. At least not when I was there. Some of that happened, or so I’m told, before I got there. Some of it happened, and this part I’m sure of, after I went back to Rome. When I met my Italian photographer friend in Venice in the summer of 2014 we spent an afternoon looking for dead people on the Isola di San Michele. (Ezra Pound, Igor Stravinsky: still dead.) That night we—the Italian photographer, his American girlfriend and I—did go on a boat with one Venetian. He took us to an abandoned island the locals use as a rave site. I’m not sure if the island had a name but there was a hand-painted sign that read: DISAGIO. I saw lagoon rats the size of baby zebras. It was a luna piena. The Italians and the American drank beer and prosecco while I drank water and the tiger mosquitoes drank me. Nothing happened. We stared at the lagoon and stared at Venice while they spoke about American rap music and Venetian politics. I was too tired to speak bad Italian so I just stared between the lagoon and the moon and quit fighting off the zanzare. The Italian photographer put his arm on my shoulder and said: You know, we’re looking at the same thing Marco Polo looked at.