by AARON AYSCOUGH

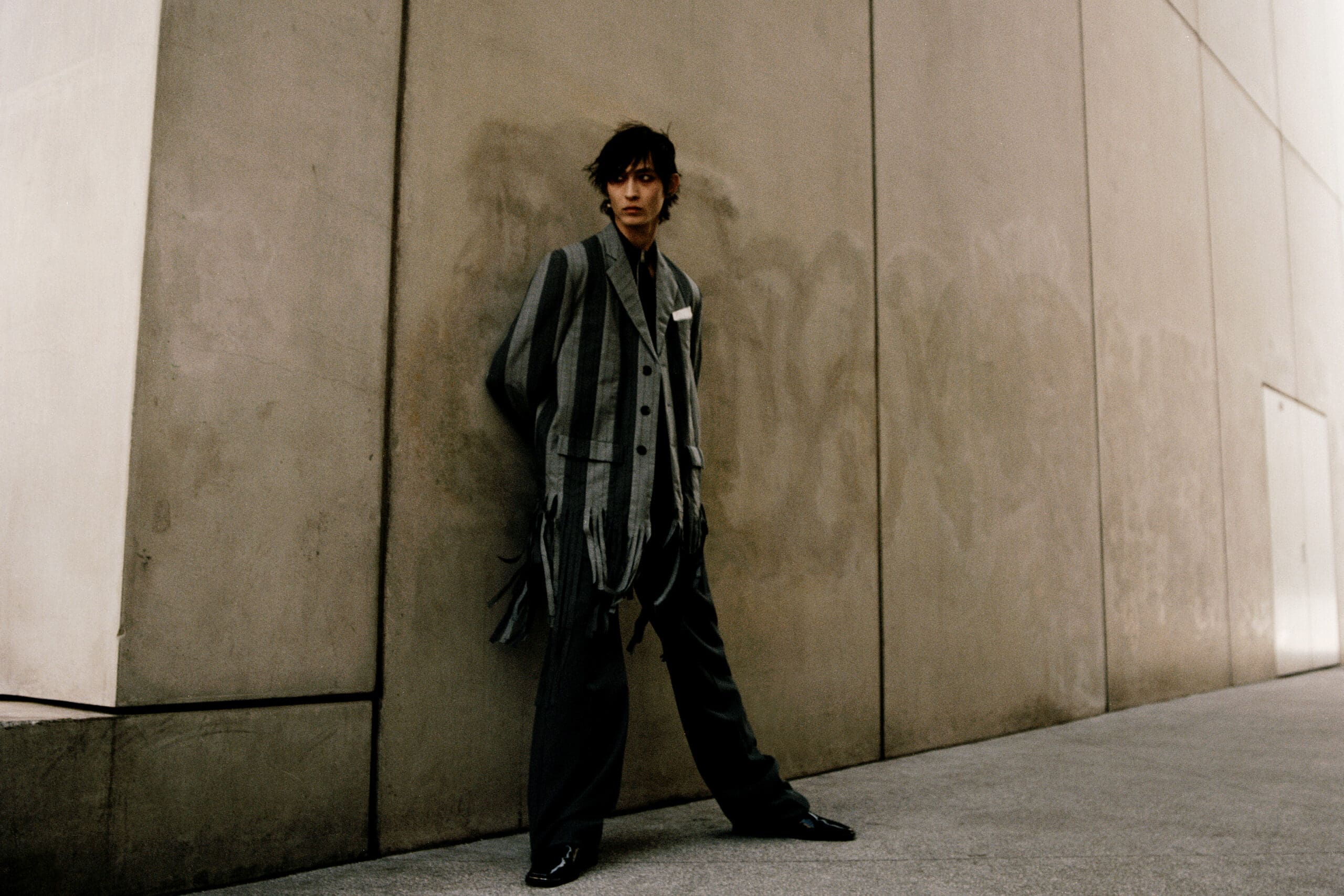

photography ARYANÀ FRANCESCA URBANI

coordination MARIAELENA MORELLI

30 November 2013

Perfume, Language, Possession: An Interview with Serge Lutens

At one point during my interview with renowned perfumer, photographer, filmmaker and make-up artist Serge Lutens, he senses a lull in conversation, and asks, as if commenting upon the weather, whether anyone present has ever considered suicide.

He’s not being morbid. One just gets the impression he likes the transgressive effect of the language of suicide in the context of an interview about a perfume launch. Lutens had granted interviews for the pre-release of “Laine de Verre,” a quasi-industrial raw-aldehyde / cashmeran-based eau de parfum that will see Paris release in February 2014 and international release a month later. “Laine de Verre” caps a recent triptych of eaux that also includes last years’ evocatively-titled “La Fille de Berlin” and “La Vierge de Fer.” (“The Girl from Berlin” and “The Virgin of Iron,” respectively.)

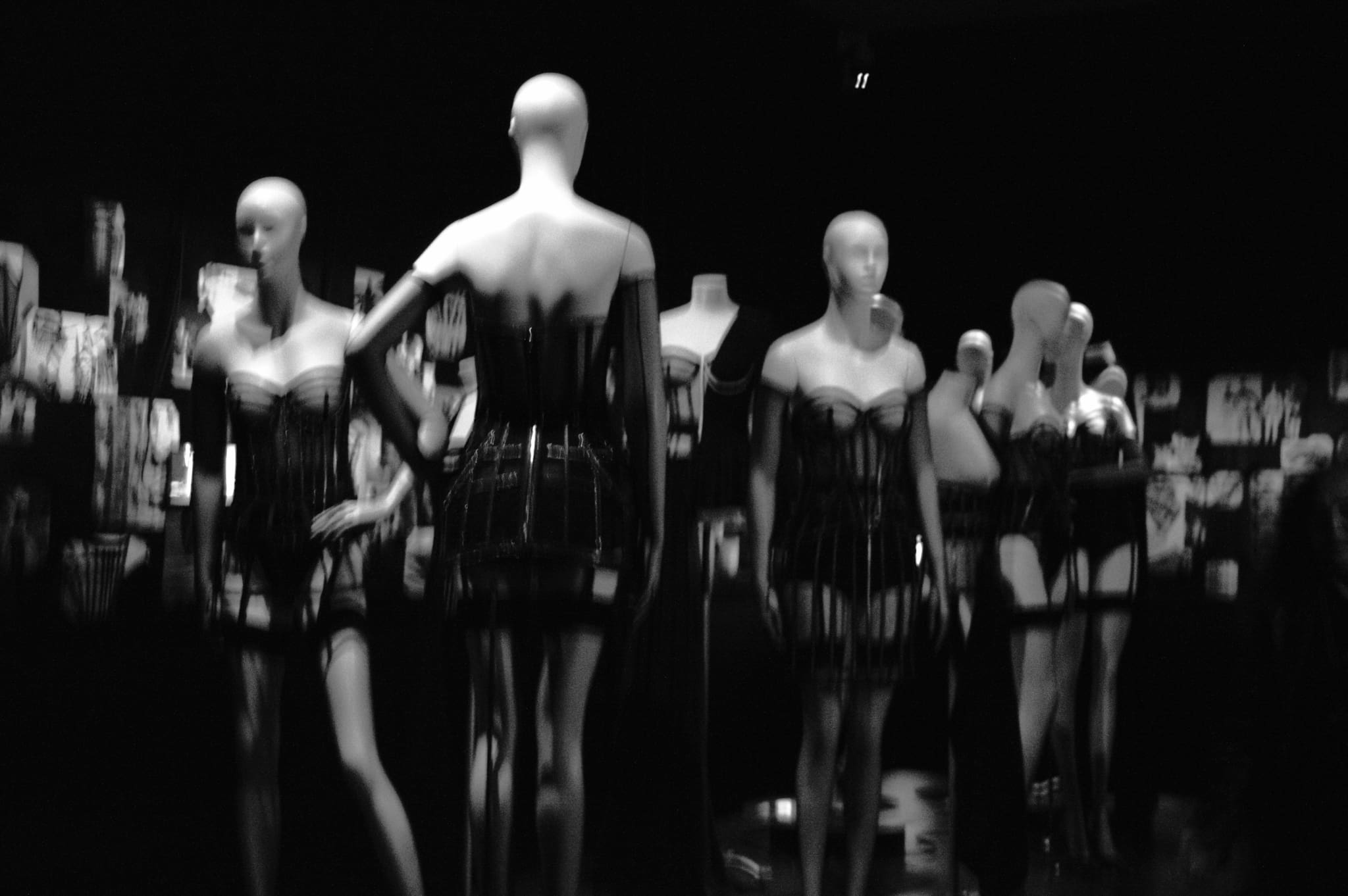

Lutens thinks a lot about language and its effect on our senses. All his perfumes—from the legendary, now discontinued “Nombre Noir” in 1982, to his groundbreaking “Feminité du Bois” for Shiseido in 1992, to “Laine de Verre”—share a distinctly literary taste for the ostensible paradox. He asks us to consider the femininity of wood, or a wool made of glass, and thereby stimulates physical senses via cerebral means. A self-confessed “obsessive,” he views his creations as reiterations of a single idea, one he’s pursued throughout his charmed career since his troubled childhood in Lille during WWII. In Lutens’ telling, he invented a woman, and that woman was both him, and at once, his estranged mother, and having created this woman, he kept recreating her in every subsequent medium.

None present for the GREY interview has contemplated suicide, or none will admit to having done so. But everyone responds lightly, encouraged by Lutens’ own unflappable gentility. At 71 years old, with an immaculate white collar shining from beneath the black wool of his tucked-in cardigan, Lutens resembles nothing so much as beloved American TV personality Fred Rogers, had Mister Rogers chosen to engage somewhat more adult subjects: sense-memory, gender identity, and the Freudian basis of most luxury marketing.

You’ve written that your new perfume, “Laine de Verre,” is inspired by “complementary opposites.” What are these?

The conflict is in me. There’s the feminine conflict, and the masculine conflict. I bear them both… There is a conflict, because there is something in us that we don’t want to touch, that we don’t want to change. Nothing is more fixed than the choice of an infant. All the choices—we make them before seven years of age. The age of reason: between seven and ten years’. The choices are made, it’s over, it’s done. Our choices, our orientations, our tastes, our ways of thinking, our ways of seeing.

It’s Proustian, the idea that our early experiences influence our aesthetics later in life.

It’s Freudian too, necessarily. But even before him we knew this well. It’s during adolescence that we have all the revelations of our selves.

Do you have specific memories linked to the scents in “Laine de Verre”?

Yes, because it’s my life!

I was born in 1942. It was the war. I was born in Lille in the north. France was occupied. My mother was an adulteress. I was a natural child. I was therefore, for the sake of my mother’s security and mine, separated from her, because otherwise she was endangered. The Loi Pétain forbade [adultery]. It was the Vichy government, for the sake of the purity of the German race…

So I invent a woman. I invent her…and I multiply her… It was my mother. It was a love story at first. But since all great loves are impossible, it wasn’t true. So that’s what happens—I invent a woman, and I multiply her. I multiply in my images first, in photography, and then in perfume, in decoration, in dresses, in make-up… But it’s not relevant. It’s not what I did, it’s what [what I did] means… Very often we speak about products and perfume and people say they’re revolutionary, but it’s not that. It’s not the products that are revolutionary. It’s the revolution that occurs in me each time that leads me to make a product, an image, something that must go farther, that must convey me.

In 2012, you launched a website to offer your entire perfume range to the US market, even the perfumes previously exclusive to the store at the Palais Royal in Paris. What motivated the decision?

The bottles at the Palais Royal shop were designed uniquely for the Palais Royal in Paris. I didn’t want them to move. But the commerce—the business—it’s obligatory. I don’t think it’s good that the perfumes move elsewhere. But anyway from the moment they move, they no longer interest me. So I must find another solution… That’s what interests me, to develop… We’re in Barney’s in New York as well. They ask me [for the perfumes]. I reply: “I don’t care.”

Because it’s true. I won’t die because there’s a bottle there or here. And more and more I find it very stupid to create prestige via limitation. It’s a little jerkish. It’s as if prestige were to be found nowhere. What is exclusive, is us. It’s you. It’s you who are as a person, who chooses. If something is difficult or hard to find, it’s not that which confers value for me…

Yet, in a quote often attributed to you, you said, “Luxury is the distance (the greater the distance between you and the object, the more luxurious)”?

Oh, I say so many things. Sometimes I say anything… Luxury is us. It’s yours, it’s mine. This entity, what we call luxury, annoys me. I don’t like it. I don’t like the name. The idea of a luxury—what is it ? Just the other day I was with an art dealer, and we spoke of collectors. The collections. One says you have the collection of this, of that. There is an eroticism of discovery, of buying, to possess, it’s pure erotism. But I tell myself, I’m not a collector. I’m just obsessed. It’s similar. We put a canvas on a wall for an idea of something we like. But as soon as it’s put on the wall, we’re no longer interested. We become its keepers. What do you want when you’ve seen something ten times? You check to see if it’s still there, if it’s still yours. It’s possessiveness…

But this possession doesn’t speak to us after a while. It’s mute. What do we care about that? It’s a sort of—excuse me—dry masturbation… There are collectors who are going still to buy, to accumulate, the same thing a thousand times. Like antiques. But I don’t believe in it.

The idea of possession is interesting in relation to scents. Do you think it’s possible to truly possess a scent?

I believe that perfume is an intermediary. For example, you have a fashion of dressing. A chosen way of dressing, your jacket, your choice, your comportment, it’s an intermediary too. Now, we only smell perfume for 3 minutes. We choose it. It’s like a haircut. You see it in the mornings you say, okay, that’s how I’ll be. You have an image of yourself. That image, during the day, will dilute itself. You’re dealing with others, but you see that it works, that people respond. I call it an intermediary. A perfume for me is someone that passes between us, who does the relay.

You spend most of your time in Morocco these days. Are there certain scents that appeal to you in the context of Morocco, but not, for instance, in Paris?

In Morocco, scents are very present. It’s the first thing you notice, it calls you. But that’s not what creates a perfume. What creates a perfume is olfactory memory, what we have known, it’s almost the same thing. You’ve lived vanilla, cinnamon, you’ve lived the scents… We have very different experiences, but the panoply of olfactory sensations is the same. Before we’re seven years old we record 500,000 scents. It’s a box. These 500,000 scents will be diffused throughout hundreds of millions of other scents. But in all those scents that you’ll smell, it’s always something that you recognize from that box of 500,000, otherwise you’ll hate it. It’s not whether something is good or bad, it’s whether you find something again that you’ve lived…

I knew a girl—it was [the radio station] France Culture who brought her to me. She had no sense of smell. When she’d played with friends at school, and the children said something smelled good or bad, she followed, but she didn’t know what they meant. She was very beautiful, but as if her face were completely shut off. France Culture came to ask me to choose her a perfume. It was very wicked, in retrospect.

She was pretty, she had a good face, she looked like Simonetta Vespucci, who is there at Musée de Fontainebleau with her little snake, who worked with Botticelli… [Vespucci] also posed for Michaelangelo, all the painters and sculptors of the epoch… Her husband didn’t like women, so she had a lot of time to pose. She died at 23 years old because she decolored her hair, like all the sophisticated ladies of Florence, not by the light of sun, which was vulgar, but by the light of the moon. There were big vents in the house to let in the light of the moon on the hair, but for it to work perfectly, the hair had to be wet, with a little bit of oxygen. So she stayed like that and she caught tuberculosis and died very young.

So this girl, when I saw her, she immediately made me think of this woman—not in her life, but in her beauty. She had a very straight nose, she was very beautiful, very symmetrical… And she was monstrously boring. I said what do I do? I alighted upon this story of Simonetta Vespucci. I told her the story of Simonetta, who used a powder of iris perfume, and the story of the prince, the two Medici brothers who were crazy in love with her, and all the painters for whom she’d posed. I saw that this story [impressed her]. And this was her perfume. I invented her perfume with words. Because it was more important for her to know what she would sense through the words. And it was very moving, a very pretty story.