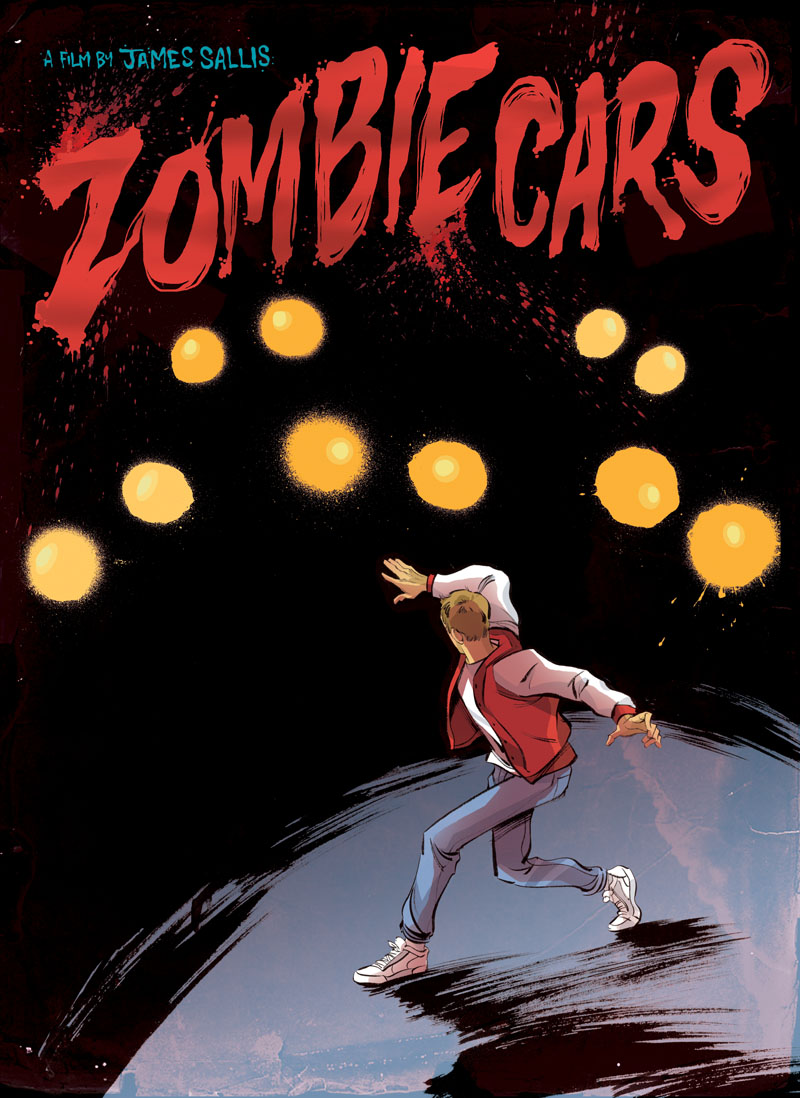

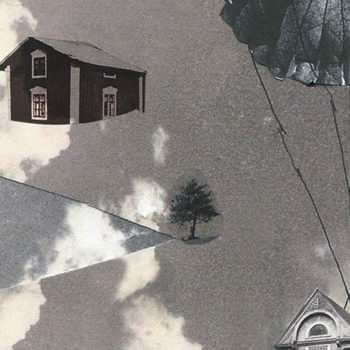

by JAMES SALLIS

illustrator KAGAN MCLEOD

ISSUE VI

Turn the clocks forward eighty years.

Oil resources are depleted, the cities have emptied, much of America has returned to rural living. Rumors begin to circulate, then “unconfirmed reports” by media: old cars and trucks are rising up from the ground and from wrecking yards like zombies of old, losing parts and drooling fluids as they move toward centers of population seeking gasoline and oil.

Little is remembered of the ancient technology.

But outside Iowa City, where the Amish have grown affluent producing buggies for the entire country, one boy knows about the old vehicles. Ridiculed as “car crazy” by peers, an exasperation to his single mother, he is obsessed by automobiles and the culture they engendered, his room filled to bursting with photos of classic cars, drive-in restaurants, filling stations and racetracks, his shelves sparsely but lovingly stacked with copies of Hot Rod Magazine and ancient books hunted down and purchased with the money he makes as an apprentice farrier.

Finally the reports can no longer be denied. The revenant vehicles are everywhere, lurching toward Bethlehem, Des Moines, Keokuk, and Cedar Rapids.

“Yet again the wretched excesses of our past come back to plague us,” a politician says on an election swing through St. Louis.

“Who would have thought undeath had done so many,” a poet intones at a rally near Gary, Indiana.

“We must reach down, down deep, to find the carburetor and differential within us,” a lay preacher implores from a Wisconsin pulpit.

And in a farmhouse outside Iowa City, the one person who just knows he can help, has to make the decision of his life: To go against his mother’s explicit orders, or to save mankind.

Meanwhile, among the revenants, factions develop, some crusading to wipe out the humans to whom they owe their existence, others to accommodate and co-exist. My personal favorite scene is a revival meeting held in the ruins of a drive-in theatre, a Ford F-150 truck preaching to a field of vehicles who hear his sermon and entreaties both through the malfunctioning speakers on stands and through the cracked speakers of their own radios (Throughout, the vehicles speak with sound: motors, creaks, horns. Translations appear as subtitles.)

Another pivotal scene has Tim sitting in his room reading. He is listening to news about the zombie cars on a crystal radio he’s built into an ancient plastic model Thunderbird; from time to time he turns off the volume to hear, in the distance, the rumble of vehicles reviving and extricating themselves from the wrecking yard miles away. He is reading the end of Gulliver’s Travels, where Gulliver, after his time with the Houyhnhnms, has become a misfit amongst his own, passing his time chatting with horses in the stables.

Finally Tim makes his decision, leaves a note for his mother, and strikes out, with a change of underwear, a Popular Mechanics guide and mechanic’s tools bundled into a bag at the end of a stick, as he’s seen in pictures of hobos.

He knows he can help. No doubt about it, none at all. Just isn’t sure how.

Following a number of encounters with humans and revenant vehicles, he almost becomes collateral damage in a zombie-human stand-off but is rescued by a renegade zombie, a psychedelic painted VW van. The van once belonged (“for a long, long time—if, of course, you believe in time”) to a philosopher, and has learned to communicate through its radio speaker.

Together Tim and the van, who Tim decides has to be named Gogh, find their way through battling humans and revenants, lone wolf vigilante humans, and splinter groups including a small troop of revenant vehicles repeatedly “killing” themselves for the greater good, only to be again reborn. Eventually Tim and van Gogh encounter and join others like themselves, humans and vehicles who have formed alliances.

The way of the future, they all begin to understand, will not be one or the other—soft machine, hard machine, living, unloving—but both.

“We’re not locked into Aristotelian logic like you,” Martin explains to Tim in one of his frequent philosophical musings, “we’re not locked into logic at all. It’s not either/or, Tim. It’s all one big and. Always has been.”

A shrewd critic* has written that in science fiction two endings are possible: either you blow up the world, or things go back to how they were before. Ever the team for challenge, for going that extra inch or two, and for utterly ignoring the reasonable, we figured out a way to do both – so don’t miss Zombie Cars when it comes clanking and leaking to a theater near you.

* me