by Cheryl Cardiff

illustrator Carolina Melis

22 April 2013

TAG 6: RUNDGANG AUF DEM GELÄNDE DER PETER-PAUL-FESTUNG

They were all that they had left in a neighborhood of rubble and dead children. Eva laid down beside him and hugged him tightly to her as if she were assuring herself that he at least was still there. Not a phantasm, but alive and of real flesh.

“Say, Bruno, do you miss Rudi?”

Bruno said, “Yes.”

“That’s good,” she said, “you should.”

He didn’t mind her being so close. Eva was always affectionate with him. Her daughter was dead, and Bruno felt even more sorry for her than he was for himself.

“Do you think Rudi will recognize me when he comes back? I wonder about that a lot. I wonder if he’d be able to pick me out still if I were standing in a crowd of people.”

For some time now, she had been saying how she didn’t look the same anymore. How she wasn’t pretty anymore. He would catch Eva looking at her own reflection, her frown an admixture of worry and self-condescension, and hear her talk to herself. Maybe that was what she had been saying all along: How on earth will he be able to pick me out of a crowd?

Rudi heard Eva whimper for herself now. Then, in a voice that made her sound younger than she actually was, Eva asked, “Do you think I’m still pretty, Bruno?”

Bruno didn’t say anything. Instead, he drew his knees up to his chest, curling himself up like a ball.

“I shouldn’t ask you such things,” Eva said, a gentle tone of apology in her voice. She touched his back with the flat of her hand. “May we be friends again?”

He nodded. The truth of it was that he desired somehow for Eva to have her way with him. For some time, his curiosity about the opposite sex, about the whole thing, about her body, became manifest. It didn’t help matters that the boys were talking about it. That was all that they talked about really. Bruno had been ashamed of himself. Now, for example, his curling himself up into a ball was a way for him to hide that. Eva inched her body to his and wrapped her arms around him. Bruno both was excited and terrified.

She draped her right arm over him, the skin of it so thin that he could see the fine blue-green vein on her wrist and the flash of gold downy hair toward the elbow. He ran a gentle hand over the length of his arm.

“I think you still are pretty,” he told her.

“That’s nice, what you said to me just now.”

Rudi had come home six years after the war ended. Neither he nor Eva recognized him at first. At home he seemed still caught in the war he had come out of. He woke up nights, in tears, and they could not imagine the kind of nightmares he was having. It terrified Eva completely, having to share a bed with a deranged man.

The night Rudi left them would forever remain in Bruno’s life like a brand burned into his soul. He had found his brother sitting alone in the dark. It pained him to see Rudi, looking out the window, a creature of deep anguish, bewildered like a child and haunted like a man at the same time.

“Do you remember when you and I looked up at the sky last?” Bruno asked him, pointing to the night sky outside the window.

Rudi shook his head.

“That was the night when I smoked my first cigarette, remember?”

But he didn’t remember.

“Mother would have had both of our hides had she found out,” he laughed softly. “But now you’re here finally, and I feel that all finally is what it used to be.”

He watched his brother’s face soften. Tears limned Rudi’s eyes silver. Bruno, himself moved, patted his brother’s shoulder heartily.

Rudi shook his head. “It’s not as it used to be, Bruno.”

Bruno chuckled, “Well, that’s true. But things have changed. For the better I feel.”

His brother cracked an unexpected smile, surprising Bruno. Even Rudi’s smile, which had charmed the women in the neighborhood—young and old—wasn’t as it once was. His smile seemed only tacked on, forced onto an unwilling face.

“How is it that you can delude yourself, brother?”

Rudi had said this so amiably that Bruno decided he was joking with him.

“Always such a kidder you are, Rudi. Just like old times.”

“You and Eva carry on, believing as if this were home still. You think the same houses, the same trees, the same sky, the same people—well then, it must be the same.”

“Of course it is. It’s home.”

Rudi took his head in both of his hands as if to crush it. “Then why don’t I feel at home?

Bruno began to tremble. He backed away, afraid that Rudi might strike or lash out.

“I hate this place, you understand? No, of course you don’t. Willing, happy fools that you all are.”

“What do you mean, you selfish man,” Bruno argued. “You sit there and think you can judge all of us. I saw everyone we knew die or change completely. We’ve worked hard for this. That’s all we wanted was our home back. We’ve deserved this.”

“Oh, Bruno, what are you talking about? Because you all think so long as you have your complacency then everything is fine. It doesn’t matter with whom you’ve bargained for it

“You don’t know what you’re saying.”

“Because I’m crazy, right? That’s what you think. So what if I am? I’ve a right to be. You tell me I’m home. You try to convince me how everything is the same. But I know they’re not the same. It’s not what I remember them to be in here,” he insisted, pointing to his head and heart. “They’re not real.”

“And I suppose I’m not real? Eva’s not real?”

Disgusted, Rudi waved him away. But Bruno was firm on his course. He wasn’t a little boy anymore, for Rudi to dismiss him so easily.

“This is home,” he insisted.

“It feels wrong, Bruno.”

“What would you rather? Would you rather waste away somewhere else with no one who knew you, without a family to love you and understand you?”

Under the moonlight, the shadow of the window frame fell on Rudi’s body, quartering him. “I’d rather be dead than be in on something so wrong.”

“Selfish man. We worked hard to make this all right for you. And what do you give us in return? Ingratitude. Semantics.”

It was then that Rudi looked up at him. He didn’t seem hurt by what Bruno said.

“Whatever faith you may have now will fail you one day, Bruno. And greatly.”

“And what of you, Rudi? You left Eva. You left your daughter. You left mother and father. You left me. We did the best we could, endured what we could while you were gone. Now you come back, feel you are owed something, and spit at what we try to give you because it’s not to your liking. Maybe it’s you who has betrayed all of us, did you ever think of that?”

Rudi remained silent.

“Are you so determined to remain dead inside if you can’t have what it is you want, exactly as you want it?”

“You’ve changed, Bruno.”

“I’m a man, Rudi.”

“You’re not even that,” Rudi said gravely.

Bruno bit his lip, wanting to beat him out of his senses for such an insult. He left Rudi for his room, his head pounding as hard as his heart.

Sometime during the night, Bruno could hear Rudi shuffling around the house. Then the sound of a door downstairs opened and closed. He got out of bed quietly and tiptoed to his bedroom window. In the moonlight, he saw Rudi’s gaunt figure emerge like a flint. Rudi was dressed, his traveling case in his right hand. As Bruno saw him walk, not once did Rudi turn around. Despite the fact that he had wanted to call out to him and ask for his forgiveness, Bruno Schlink’s pride got the best of him. He watched him disappear from view. When he turned around, he was surprised to see the figure of Eva standing by the doorway to his room. In the near dark, they didn’t speak to each other for a very long time. But there was certainly something tenable in the space between them. Something certain. Agreement. Eva wasn’t going to call out to Rudi either. She turned, in the direction of her room. He could hear her footsteps as she returned to bed.

A year later, Bruno received a parcel containing all of Rudi’s letters that he had written to him. It had been sent from an address in the West. There were twenty-two letters in all, written within a six-month period. Immediately, he knew the handwriting to be Rudi’s. He didn’t read them, not one. He’d grown so bitter over his brother’s leaving that it seemed to him easier to fuel his disgruntlement than lay it aside. That a man should so disown the place of his birth? he thought to himself, enraged. That he should run off to the West? This was the greatest insult. This to him was not the makings of a man, but a coward. Bruno burned the letters, what memory he had of where Rudi had ended up and where it was. Bruno burned them all, including the envelope and string they came wrapped in.

Bruno Schlink shuffled around in the half-dark and light of his hotel room while his grandchildren slept. He was gathering things, folding shirts and pants, and packing them away. As he had done in the past four days, he set aside a new set of clothes for Willy to wear tomorrow. In the past two days, he had been doing the same for Gitte.

Gitte started to snore lightly. He left the bathroom light on in case either of the children should wake up. Keys in hand, he slipped out of his room and headed for Eva’s room.

There was a slip of orange at the foot of the door. Bruno Schlink thought that she was awake so he knocked at first. There was no answer. After a while, he entered the room and found Eva fast asleep.

Bruno stood over his sleeping wife and looked at her for quite some time. Her blond hair, which she still wore long, had turned to an unbecoming grey. So, too, her eyebrows that fanned out at times that Eva developed an unconscious habit of quickly licking her index fingers and combing them over her brows to tame them back into place. Her thin lips were parted, baring the incisor that she had chipped long ago when she was a teenager, and there was a faint trace of spittle on the right corner of her mouth. Her face, the way it looked to him now, reminded him of the first night of their lovemaking, the sense memory of which he had whittled down to rank body odors and the grunting noises he made.

Afterward, he had found himself thinking that he had expected something more. Something wonderful maybe. Something to the extent of the smell of fresh cherries that greeted one when coming upon Frau Bammer’s presence. But the act, once they had done it, hadn’t felt fresh. Rather, it felt desperate, like people clinging to a tree to keep from drowning. And although Eva was as warm as a hearth inside, Bruno couldn’t help but be reminded of how cold his buttocks were. How cold and indifferent her belly was to his. Twice he tried to reach for her breasts. Eva grabbed his hands and squeezed them so tightly into hers that Bruno winced, thinking that the skin between them would tear. Afterward, when she had rolled away from him and mumbled something he couldn’t understand, he studied her back, her spine like a range of shallow hills the color of bread dough. He studied her shoulder blades, and the frightening and vulgar dip of her skin below her rib cage.

As he stood over Eva, Bruno Schlink seemed still bewildered at how easy it was for him to have made his choices, how easy it was for him to turn the page and keep on going. It took will on his part, but even that came easy. He didn’t have to wonder when it was that the longing to see his brother came to an end. Eva had some will but none long-lasting really. The Wall certainly made it easier. And when the Wall came down, well, he was an old man at that point who, from experience, could say that he had seen enough to know that there were just some things that remained permanently divided and unresolved in the world.

“Hateful, hateful man,” Bruno muttered to himself. Only Eva knew the truth.

“What is it?”

Eva had woken up and now was staring at him. Bruno wondered whether she recognized him.

“It’s me,” Bruno answered.

“Well, of course it’s you, silly. Rudi, look in on Gitte, will you? Make sure she’s warm enough before sending her out into the storm and cold.”

She was in her waking dream again. The one where she lived in a different life. The one where she was still with Rudi. The one where her daughter had grown old enough to go to school.

“Will you do that?” she asked him.

“Yes, I will,” Bruno told her.

Eva smiled.

“Go back to sleep now, Eva.”

Eva nodded and closed her eyes, an easy smile across her face.

TAG 7: TRANSFER ZUM FLUGHAFEN UND RÜCKFLUG NACH DEUTSCHLAND

They were heading back home to Germany on an 8:30 flight out of Sankt Petersburg. It was a Saturday morning. The clouds that hovered over the city were now making good their threat. The big drops of rain might as well have been ice; they practically stung their skin as they hurried to the bus. Bruno saw Eva’s face smiling as she grasped Gitte’s hand, letting her granddaughter hop over the tiny pools of water that were forming. Everyone was upbeat enough. The West Germans were laughing it up, “Ho-ho, we’re leaving just in time. We’ve taken what sunshine these Russians have and now they’ll be mad at us surely.”

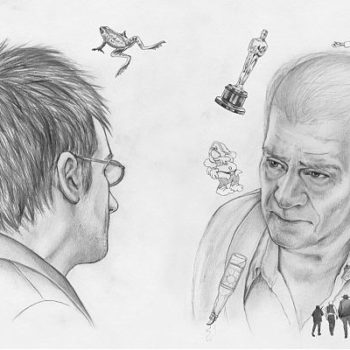

When Bruno raised his head after he made his first step getting into the bus, Natasha Petrova was there. But she was busy talking to the young Asian girl who had spoken with Bruno Schlink earlier in the week. He looked quickly away to avoid having to meet Natasha Petrova’s eyes; he was still a little ashamed for his behavior. The bus filled with chatting and more laughter. Bruno Schlink smiled vaguely. He sighed and scanned the walls and windows of the bus for no reason other than to appear busy and briefly glanced over to where the Americans were seated. The American’s wife had her head on his shoulder, and her hands were wrapped around the thick part of his arm. They were both looking out of the window contentedly.

Bruno didn’t dare consider Eva already seated next to Gitte, trying to straighten out her damp hair. Gitte, who worried about Eva, now minded her grandmother more than ever. She sat stoically, silently wincing every now and then with each tug of her hair, without complaint or crying out.

“So when was it that your first little girl left, Oma? Was it yesterday?” Gitte brightened suddenly.

“Not now, Gitte girl,” Eva said with a light harsh tone in her voice. “Your Oma is busy combing out your naughty hair.”

They drove through the Nevski Prospect once again, this time out of the city. The streets were as empty as they had found them at the beginning of their trip. They all knew better now about why that was of course. Weekends were spent with the families, which was why there were no cars on the streets. No traffic. No pedestrians. No shopkeepers. No shopping. They wound their way to the outskirts of the suburbs, to the less attractive parts of Sankt Petersburg, they remarked silently to themselves. Was it right that visitors to the city had to be driven through here at all? It didn’t seem fair that they should find themselves shaking their heads disappointedly at the things they saw. The abandoned fields. The trash. The graffiti. It was as if all that had been wonderful had never happened to them and that the photographs they took were nothing more than imaginary places fit for children’s fairy tale picture books.