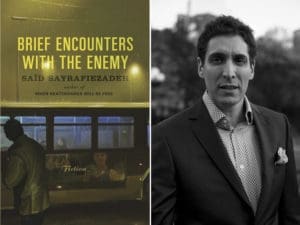

by Aaron Akira

illustrator Simon Pemberton

11 November 2013

A man of different temperament might have been displeased to travel so far alone in a foreign land. But the messenger Renty enjoyed the time for reflection his excursions permitted. That his first loaned horse had proved lame bothered him not a bit; he was, on the contrary, grateful to have a reason to interact with the villagers in the next town he passed. He strolled around that village as its blacksmith re-shod his horse, aware that the new horse hadn’t needed re-shoeing and that he was, as it were, being hosed by his hosts, the villagers.

His destination was the Portuguese King John’s winter court at Estremoz, just under three days’ journey from Lisbon on horseback. He reckoned he could safely make the journey last five days. A given distance, he was at times obliged to explain to his superiors, was like the purity of a man’s heart. One could make guesses, but under no circumstances could one truly measure it. That was God’s domaine. There were many contingencies apt to delay a messenger, or even prevent him entirely from ever reaching his destination : inclement weather, flooding, swarms of insects, rockslides, bandits, feverish horses with teeth like cobblestones… There were days when Renty felt that the air itself grew heavy, somehow thickened, like an overstarched sauce, such that even riding well-trod roads felt like fording a river…

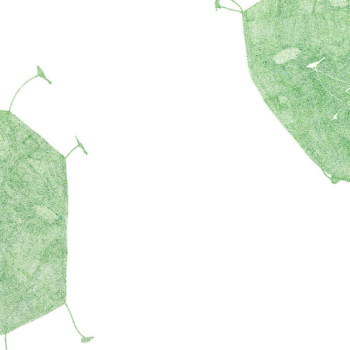

Today, he had been waylaid first by a lame horse, and next, as he waited among the villages’ rough-hewn, marble-clad structures, by lavender. Bales of lavender. He had never seen the flower preserved in such quantities as in one central building, where it hung from rafters in great boughs, was fused into mountainous cakes of pale soap, as if for the toilets of giants. One old man who seemed central to the local industry approached Renty, seemingly struck by the latter’s ducal livery. Though the man spoke neither French nor Latin, Renty succeeded in holding his attention for almost thirty minutes, sampling numerous lavender balms. The old man gave Renty to understand that one oily balm in particular was essential for strengthening hair follicles. In a fit of indulgence, Renty purchased some, only to consider later that the balm would almost certainly not survive until he next saw his wife back in Lille. It could take years – there was, as he had tearfully explained to her before setting off on the Duke’s marriage delegation, no real measuring it…

This was both true and not true, he reflected, as he made his way back to the blacksmith’s.

There was one surefire way of measuring the efficacy and devotion of a messenger. It was to dispatch, separately, two messengers. In the case of Cecille back in Lille this was, of course, impossible; he was her only husband. But Duke Philip had been known to test his messengers in this way. It was for this very reason that Renty had had the foresight, upon exiting the castle gates in Lisbon, to hide in a hedge outside for almost a whole day, surveilling the gates for the exit of a second messenger. None had appeared. So it had been with a buoyant heart that he’d finally set out for Estremoz, more or less safe in the knowledge that the journey could take as long as he saw necessary. He lingered over the rich “horse mackerel” soup he purchased at lunchtimes. He sampled the coal-black local wines. With every passing stranger he attempted to communicate his feelings about their land and its customs, and he found he had much to say. For the time he spent on solitary missions, such as the one he now conducted, bearing the preliminary salutations of a marriage proposal to King John’s daughter, was the only time he truly enjoyed. Life itself, at such moments, seemed a bonus. His will was at once his own, and yet not; his duties, like Cecille, awaited him, and to both his faith was wholly voluntary, if intermittent. Leisure ennobled Renty. He fancied that, without it, there was no good in man – only obligation, fear of immediate reprisal.

He would, after all, reach Estremoz by and by. He would be struck by its uniform pink marble, the salmon-tint of perpetual sunset, and the chasms quarried from the surrounding landscape. And the time he spent waiting for news of his arrival to be conveyed through the echoing marble corridors to where King John sat ensconced in velvet would seem longer than the entire journey until then, though, he thought happily, nowhere near as long as the journey still to come.