by Saïd Sayrafiezadeh

illustrator Paula Castro

Issue III

There is a man in the public library who looks at internet pornography. Thomas Smith noticed him just a few minutes after he noticed the pretty librarian with the strawberry blonde hair. And because these two observations came one right after the other, and because they came right after Thomas Smith had moved to the city, he would forever link attractive sophistication with abject isolation.

The library stood across the street from a sandwich truck that Thomas Smith patronized everyday on his lunch break. Even though he had been a regular for almost two months, the man who served him did not ever remember Thomas or what he ordered; what he ordered was always the same: tuna on whole wheat with a pickle. His father would have approved. (He was twenty-six and still often thought of his father and approval.) “What do you want, pal?” the man would shout over the sound of traffic; he wore an apron with a smiley face that conflicted with his personality. Staring up into the sandwich man’s face, Thomas would reflect on how it could have been a portal on a ship the man was sticking his head out of, and how the man could have been a sailor, and how the traffic could have been waves, and how the million people swimming past could have been fish.

“You can be a small fish in a big pond,” Thomas’s father had told him the day before he left, “or you can be a big fish in a small pond.” It had been intended to dissuade him from moving, or at least to reconsider, but instead it strengthened his conviction that he came from a place that used aphorisms as a way to explain life.

The sandwich was always good, always fresh, and this generally redeemed the fraught transaction. Thomas would eat it slowly, methodically, every fifteen steps a bite, while walking through the crowds back to his well-paying but exceedingly boring office job on the thirty-seventh floor of a building that had sixty-two floors and six elevator banks and a hair salon. It amazed him how congested the streets could get at lunchtime, and how so many people could move so quickly and still avoid colliding with one another. Once, however, someone had accidentally bumped into his elbow and made him drop his sandwich on the ground. Before he could turn around and demand compensation, the culprit had disappeared into the crowd. “Oh, that’s a shame, honey,” a nice old woman had said.

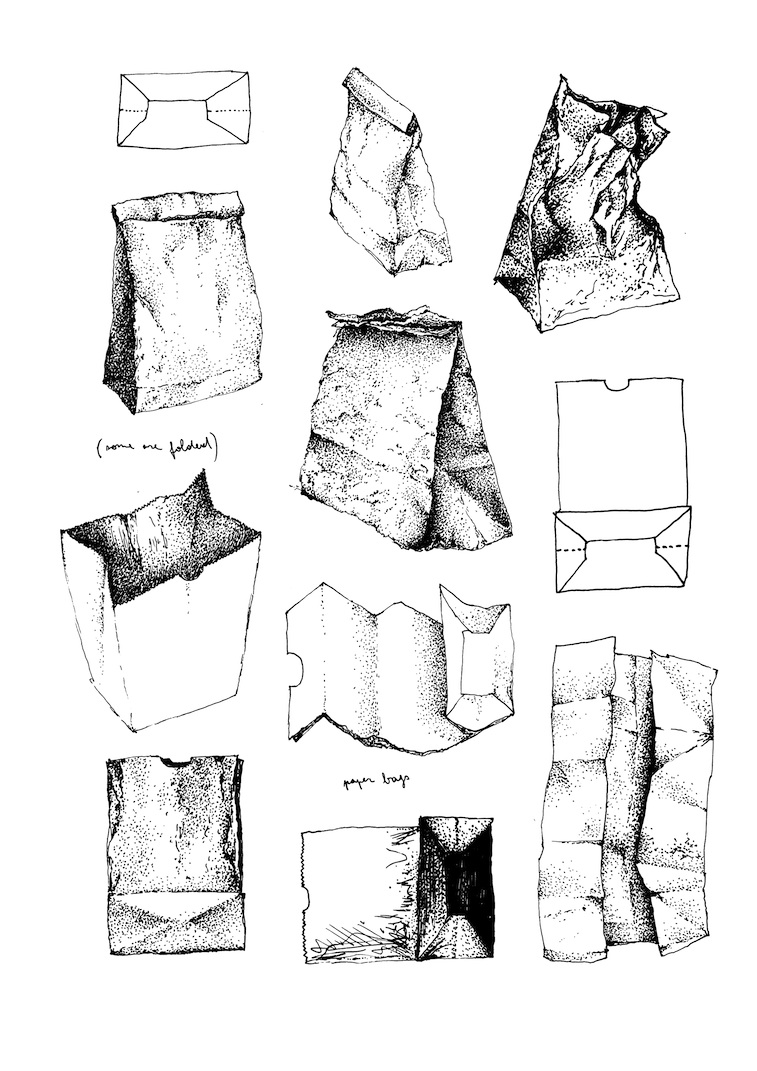

He would time it so that he would be taking the final bite the moment the elevator opened onto his firm with the glass doors and the bored receptionist, and he would move with silent steps down the carpeted hallway to his office that had his name on the door: “Thomas Smith.” Inside, he would carefully and conscientiously fold the brown paper bag the sandwich had come in and put it in his desk drawer in case he might need it for something at some point in the future. His father saved bags and so he saved bags, and he had stockpiled about forty of them so far.

It wasn’t until two months after his arrival in the city that Thomas Smith finally noticed the public library. In a land of skyscrapers it was short, and in a land of glass it was brick. It had the quality of a mushroom among Redwoods. It seemed to have survived despite itself. It looked irrelevant and antiquated. But it was February and a terrible cold front had come down from the north, and Thomas Smith, who was from a small seaside town with a warm climate, was drawn to the handmade sign hanging in the window: “Come in from the cold.” He wanted warmth primarily, but it also occurred to him that he had not read a book in a long time; it occurred to him that he had not done anything in a long time except for work. “We work to live,” his father would say, “we don’t live to work.” Never mind that his father had done the latter, managing the Sheraton and hating every minute of it, including the commute. Thomas had an inkling that he was cut out for something else in life, what that else was he didn’t know, but he knew that if he didn’t act soon and in some decisive manner he would wake up one day, forty years from now, and find himself choking on regret.

So with fifteen minutes to go on his lunch break he walked up the steps to the library. It wasn’t warm inside, it was hot. Standing in the doorway, he unzipped his coat and took it off. He was wearing a suit and this made him feel overly formal and out of place, as if he were a banker who had come to reclaim the building. In one hand he held his paper bag, and in the other he held his coat; he wondered if there was a rule against bringing a sandwich into the library, and he had a painful memory of being reprimanded by his third-grade teacher on a field trip to the museum. “Put that down, Thomas! Thomas, put that down!” But when he put it down it had spilled.

On the inside, the library looked even smaller, even more antiquated, and combined with the wood floors and the walls of books, it might easily have been someone’s living room. There were quite a few people there that afternoon, including, of course, the librarian who was at that moment shelving books in the children’s’ section. The topmost book in her arm had a cover of a turtle shaking hands with a frog, and the grave and heedful way she placed it on the shelf struck Thomas Smith as comical. He laughed. The sound was startlingly loud and when the librarian turned he saw how pretty she was. She wore cat-eye glasses and a necklace that was made out of stone or glass. Her hair was strawberry blonde, her shirt had furry wrists, and her provocative belt buckle was in the shape of the letter J. She looked like she could be about Thomas Smith’s age, but her stylishness gave her stature, as did her profession of librarian.

“Do you need help?” she asked him. She was all business.

Not knowing what to say, Thomas Smith said the first thing that came into his head. “I’m looking for plays about Greek theatre.” He hoped his inquiry would sound intelligent.

“Plays about Greek theatre?” She stared at him with concern through her cat-eye glasses. “What do you mean by that exactly?”

He didn’t know what he meant. He blushed. He took a few steps towards her to stall for time and the sound of his shoes clicking on the wood floor was disruptive to the patrons.

“Maybe you just mean Greek theatre?” she offered. She appeared to be unaffected by his stupidity, the way a doctor is unaffected by the effects of your disease no matter how gruesome.

He stared at her blankly. “Yes,” he said. “Yes, I do.”

“The theatre section is downstairs,” she said, and she directed him in a perfunctory and disappointingly detached manner to what she referred to ominously as the “sub-sub-basement.” “Three flights down,” she said, and then she turned back to her urgent shelving.

The sub-sub-basement was small, dim, and completely empty. The ceiling was low and the floor was concrete. It was hotter here than upstairs, and Thomas worried that the intense heat would aversely affect his sandwich. He had a vision of himself, amazingly vivid, vomiting into the toilet two hours from now. His shoes were even louder in the basement, they clipped like a horse, and he had to stoop low because there was a good chance he’d hit his head on the ceiling. Having no idea what exactly he was looking for, he wandered up and down the rows of books. The theatre section was situated between philosophy and history, and he had the uncomfortable insight that he knew almost nothing about any of these subjects. He could recall bits here and there, mainly from what he had been taught in those college courses that he had been required to take, but these small pieces of recollection were so scattered that they resulted in general confusion and fatigue. “Far be it for me to say,” his father had said, “but those are paths to nowhere.” Moving aimlessly among the shelves, he felt compelled to select something, anything, so that the librarian would see that he had come here with purpose, and so that he could have one more interaction with her at the checkout counter. He wondered if she found him attractive. Maybe he should get a haircut, he thought. Or maybe he should let it grow. Maybe he should ask her for her phone number. Did people in the big city ask strangers for their phone numbers? He imagined going to a movie with her at that enormous cinema that he passed on the way to work. Realizing there were less than ten minutes left in his lunch break he chose a small book that promised to be a layman’s introduction, and when he emerged from between the shelves he saw that he had not been alone.

There was a man sitting in front of the library’s public computer, and on the screen, in high detail, was the image of a naked woman with long brown hair and her legs spread wide open. The image was unequivocal, but in the context of the library it took Thomas Smith a moment to register what exactly it was he was seeing. The man sat with his hands poised on the keyboard as if he were about to type something, but he remained motionless, passive, as if he had nothing to do with the fact that there was a picture of a naked woman on his computer screen, as if the image had just appeared from out of nowhere, and all the man could do now was to stare at it helplessly until it went away. The woman stared back, smiling. Thomas Smith stared at both.

There was no view of the man’s face, but the back of him told a sufficient enough story, and the story was not a good one. He still wore his winter coat despite the oppressive heat of the basement, and beneath the coat were sloping shoulders, shoulders sloping so precipitously that it gave the impression of overall roundness, stomach roundness, face roundness, thigh roundness. This, in turn, contributed to a perception of poor sleep, bad diet, and ill health, which was borne out by the tiny amount of skin visible on the back of the man’s hands, white milky skin, greyish milk. On his round head was a blue baseball cap which made Thomas conjecture that this might be a young man going bald, or an old man already bald, or somewhere in between young and old. That inbetweenness frightened Thomas, as did the clock on the monitor that was ticking down the man’s forty-five minute allotment for use of the public computer. The man had five minutes left to go. Had he been sitting here for almost forty minutes staring at the exact same image? There was no evidence to suggest otherwise. The fact that he was in the basement added to the atmosphere of secrets, shame, hidden ideas, concealed behavior, buried impulses—all of it in something referred to as the sub-sub. This, of course, was contradicted by the very nature of the public library.

But no, apparently there was no contradiction. At the checkout counter, Thomas Smith handed over his application for his library card along with the slim introductory volume that he hoped would impress the librarian. She scanned the book with disinterest.

“I think you should know,” he said confidentially and a little like a tattletale, leaning in and trying not to look at her lips, “I think you should know that there’s a man in the basement looking at pornography.” The word pornography seemed to convey its precise meaning, so that the moment Thomas Smith spoke it aloud he had the sensation that he had just said “pussy,” and he became conscious that the strawberry librarian had a pussy, and he immediately pictured the woman on the computer screen with her legs wide open. He blushed hard. He looked at the librarian’s belt buckle in the shape of the letter J, and then he quickly looked back up into her face. She was regarding him with sympathy.

“Are you offended by pornography?” she asked.

“Offended? No,” he said, “no, I’m not offended.”

She shrugged. She smiled. Her teeth were slightly crooked and this contrasted with her perfect face. “It’s a library,” she said. “People are allowed to look at whatever they want.” Then she said, “Your book is due in three weeks.”

Four days later, Thomas Smith returned to the library. He had finished the book with limited understanding, but he was hoping that the librarian would take note of his rigor. A snowstorm, however, had dumped ten inches on the city and the librarian wasn’t there. Down in the sub-sub-basement he stood with his sandwich and his coat and read the titles of the books, and marveled again at how little he knew. Logic. Criticism. Biography. Paths to nowhere. Was it too late to become a scholar? He thought of his father’s proscriptions and prejudices, his father’s television set, his father’s job at the Sheraton. He pictured the dining room table and the chairs upholstered in red velvet, and he tried to remember something they had talked about that didn’t have at its core the topic of work, food, or the neighbors.

He selected a book at random, this one slightly larger than the previous one but with a more substantial title, which was too bad since the librarian wouldn’t be there today to be a witness. When he stepped from between the shelves he was startled to see that the grey man was there again, sitting in front of the computer. He was dressed in the same coat and the same baseball cap, and he was in the exact same position with his hands poised over the keyboard like he was about to have a new idea. On the screen was an image of a naked woman, this time she was blonde, and her back was facing the camera so that there was a clear and unobstructed view of her ass. She had her hands on her hips, her hips were cocked, and she was smiling over her shoulder and giving a wink. Thirty-five minutes remained in the man’s allotted time. “Is this your life?” Thomas Smith wanted to ask. “Is this how you spend your days?” And then a voice in his head said, “Is this how you spend your days?” Meaning, in an office on the thirty-seventh floor with a drawer full of brown paper bags.

Five days later he was back at the library, and so was the librarian. She was wearing a hat with a feather, and a purple boa draped around her shoulders. In the sub-sub-basement Thomas Smith selected a book on the basic principles of logic, and this time, when he emerged from between the shelves, he saw that there was a different man sitting at the public computer. Displayed on the screen for all to see was a Wikipedia page that concerned either a political event or a sporting event. Or a medical procedure. There were only a few minutes remaining in the man’s allotted time, and he scrolled through the entry with great industry.

Sitting in a chair just off to the side, with his legs crossed and his hat and coat on, was the grey man. He was thumbing through a National Geographic as if he had come to the sub-sub-basement to spend his afternoon exploring his varied interests in the world. It was troubling for Thomas to see that the man was a young man, about Thomas’s age, give or take, but with a slack jaw, rings under his eyes, an unshaven face, and the pallor of the unemployed. He looked as if he had been up the night before, and the night before that, and that he had eaten badly, pizza maybe. It was clear that he had all day to wait for his moment to take command of the public computer and convene with his image of the day, but lucky for him it was now his turn. He claimed the vacated seat like a bus driver taking over his shift, adjusting the height of the chair, adjusting the monitor, and in a few moments he was off and running with an Asian woman. Her legs open. Forty-five minutes to go.

Above ground, Thomas Smith stood in line at the checkout counter. The librarian was attending to a group of elementary school children who had come to the library with their teacher. She smiled at the children, and cooed over their selections, and Thomas Smith hoped that she would smile at him when it was his turn. But when it was his turn she looked at him through her cat-eye glasses and seemed not to recall him at all. She scanned his book on the basics of logic while he tried not to look at her blazing belt buckle with the letter J.

“Does your name begin with J?” he suddenly asked.

“What?” she said

“Your name,” he said, because it was too late to go back now, “does it begin with the letter J?” And he nodded at her belt buckle which meant that his eyes were in the proximity of her crotch.

“My name’s Priscilla,” she said. He had never known anyone named Priscilla, and the name struck him as decidedly old-fashioned, in the same way that the library—as a concept—struck him as old-fashioned.

“My name’s Thomas Smith,” he said.

She nodded. “Your book is due in three weeks,” she said.

The following week Thomas had to work through lunch. The work was monotonous and deadening. “We work to live…” His book went unread. He thought of Priscilla and wondered if she thought of him. He had a dream where she remembered him. He had a dream where she didn’t remember him. March arrived and it got warm. People complained about not having a spring. Then it got cold again and people complained about it being cold. That Saturday, for lack of anything better to do, Thomas Smith went back to the library. He hadn’t finished his book, but he had managed to read the first few chapters, of which he understood almost nothing. The city streets were shockingly empty. It felt like a different world, a ghost town perhaps, or a small town. A small town with enormous buildings. Perhaps a disease had wiped out the inhabitants. The sandwich truck was there, though, and the sandwich man glared at Thomas Smith through the portal as if it was his fault that he had no customers.

Priscilla was at the counter helping an elderly man. She was dressed in a flamenco dress that accentuated her ass and hips, and her strawberry blonde hair had grown longer in the week that Thomas had been away. He thought he saw her look up and smile when he walked in, but the light was hitting off her cat-eye glasses in such a way that it was impossible to tell if she was even looking at him. The library was packed with toddlers participating in a singalong. “If you’re happy and you know it clap your hands,” they sang. The singing followed Thomas downstairs where, surprisingly, the grey, milky man was not there that day. The computer sat idle. For appearances sake, Thomas chose three big books on “political events” and “historical events” and walked back upstairs. The books were heavy and the stairs made him winded. Priscilla was still helping the elderly man who apparently did not understand anything that was being said to him because the toddlers were singing with great ferocity, “Put your left foot in…”

“You have to call on Wednesday, sir,” Priscilla said.

“What’s that?” the elderly man said. “What’s that?”

She had a look of forbearance. Thomas Smith waited in line as if he also had forbearance. He wondered if her flamenco dress was an indication that she was planning to go dancing later. Did she have a handsome boyfriend who would come and meet her at the library and take her to one of those nightclubs that Thomas had always heard of.

Finally, the transaction was completed and the elderly man limped away.

Thomas Smith slid his three big books over the counter. He watched her hands take them. Her nails were painted red. “Perhaps I should say something about her nails,” he thought. But what he should say, he didn’t know. He had an inkling that if he failed to ask her out he would wake forty years from now choking on regret.

She slid the books back to him.

“Thank you,” he said with his head down.

And he heard her say quite distinctly, perhaps even seductively, “Due in three weeks, Thomas Smith.”

The sandwich man in the sandwich truck was closing up for the day, and when Thomas passed he slammed the portal closed. The sound was the only sound. There was no traffic and no people, and the avenue was so smooth and empty that Thomas could see all the way down the vast canyon of the city. Far off in the distance, maybe a mile away, was a lone figure, getting smaller as it walked slowly, very slowly, stooped and round, the unmistakable figure of the grey man. Having nothing better to do on that Saturday afternoon, Thomas Smith headed in that direction. Soon the grey man rounded a corner and disappeared, but when Thomas reached the corner and turned he could once again see the grey man walking along the blank expanse. A few blocks later he turned again, and Thomas Smith ran to catch up, dropping one of his books and kicking it into the street. Now when he turned the corner he saw that the grey man had stopped. Just like that. He was standing on the edge of the sidewalk as if the sidewalk was a diving board and the street was a swimming pool. He stood like that for a while, and then eventually he began walking again.

It was turning into early evening and the air was colder. Thomas Smith’s nose ran, the tips of his fingers stung, and he regretted having checked out three big books from the library. From arm to arm he shifted them. The books brought back the memory of Priscilla, and the way she had said, “Due in three weeks, Thomas Smith.”

“I should have asked her out right then and there,” he thought. He thought of her belt buckle.

The grey man had stopped again. To stare at something. Nothing. Thomas Smith had drawn within a few blocks, but the man seemed so oblivious to his surroundings that Thomas was confident that he would go unnoticed. Standing motionless, the grey man’s figure was caught in silhouette so that he looked like a flat cutout of circles: head, shoulders, stomach. Then he began walking again, turning left, then right. Could it even be called walking? The man seemed to be propelled by something other than his legs, as if he were only a vessel for movement. “We are zigzagging to nowhere,” Thomas Smith thought. “This man has nowhere to go.”

But finally they entered a neighborhood. The houses were big and beautiful, or had once been beautiful, but at some point had been chopped up and converted into apartments. Their exteriors showed the strain of too many tenants. It was into one of these houses that the grey man entered; he didn’t so much enter as drift. The front door closed behind him, and Thomas Smith, giving little consideration, followed after him. Looking up the stairwell he could see the man’s grey shadow moving along the wall.

Many years from now, long after Thomas Smith had finally asked the librarian out on a date, after she had said yes, after they had gone dancing at the nightclub, after they had gotten married, he would always clearly remember this day. This was the day that he had tracked a strange man through a strange city; the day he had followed him into an apartment house and up three flights of stairs; the day he had pressed his ear against the apartment door and listened. Even ten minutes later, with his ear against the door Thomas could hear nothing. Not one sound. Years from now, Thomas Smith would remember the silence.