by JULIAN GOUGH

illustrator KAGAN MCLEOD

ISSUE V

Shortly after his forced exile from Russia in 1982, Andrei Tarkovsky, the director of Stalker, Solaris and Nostalgia, met Sheryl Leach of Dallas, Texas. The recent discovery of Tarkovsky’s “lost diary” has thrown a new light on their struggle to create what eventually became a globally recognized triumph of Western culture.

September 3rd

Her scenario is impossible. I quote to her from Schopenhauer: “The fact that time flows the same way in all heads proves more conclusively than anything else that we are all dreaming the same dream; more than that: all who dream that dream are one and the same being.” She disagrees.

September 5th

She wants Barney to discuss the number five. I argue in favour of seven. We compromise on six. And yet I feel there is a more fundamental problem. The script needs more work.

September 8th

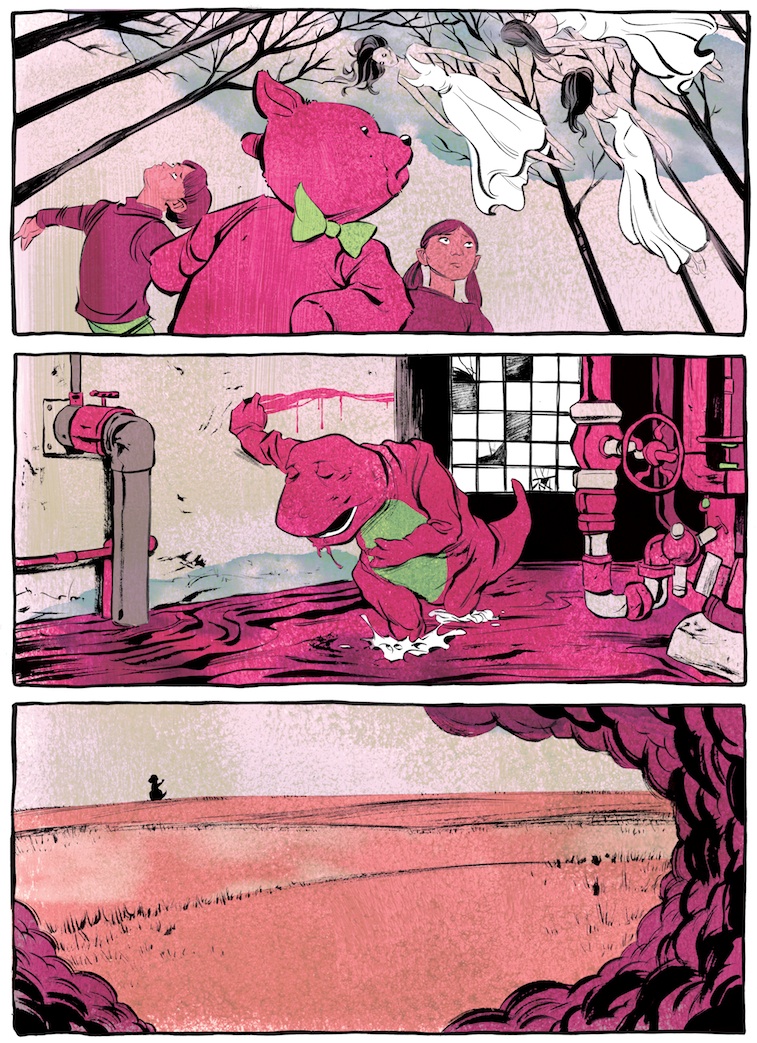

I show her my revision of her script; I have added a scene where, as Barney dances through the forest with his companions, they come across the pale corpses of their mothers, floating high in the leafless birch trees. They stop and stare up into the black trees at the white corpses. It is still, but for the drip of water and the gurgle of an unseen brook. Sheryl suggests replacing this sequence with one where Barney sings “I love you, you love me.” We argue.

September 10th

Sheryl Leach has demurred about Sven Nykvist’s wages, but I am resolute. He is the only cameraman worthy of the project. Spitefully, she responds by slashing the budget for the new sets. To placate her, I reluctantly agree to use real cathedrals—however visually inadequate—and send Sven to scout locations. And now—Now!—at the last moment, after a suggestion from her son, Sheryl Leach transforms Barney into a Tyrannosaurus Rex. Yet the leap in logic is Buñuelesque, and my soul leaps in sympathy. The innocent wisdom of children!

September 14th

Sheryl Leach obsessively presses her case, that Barney must sing “I love you, you love me.” It is as though she had never read Proust. To say “I love you”; that leap into the unknown is permissible. But to say “You love me…” This is impossible, despicable, an arrogant narcissism. “We cannot know and we cannot be known.”

September 18th

I have rewritten the scene. Now Barney approaches the children, but his statement, “I love you,” is followed by a deathly silence in which can be heard only the dripping of water, the breathing of the moist earth.

September 26th

Finally, a breakthrough. I wake in the night realising that if Barney is to live, and not be a mere “character,” then he must be true to his essence. He is a carnivore, who tries to deny his own nature, who attempts to live among children. “The lion shall lie down with the lamb.” But that is a vision of the next world: in this imperfect and sinful realm, Barney wakes one morning to find he has eaten his young companions. The bulk of the episode should deal with his remorse. He makes his way to a flooded chemical plant where his dreams and memories torment him. Sven has found a suitable abandoned industrial site on the outskirts of Detroit. I am very excited. I show Sheryl Leach the storyboards for this sequence, but there is something in her which is weak, which will not see through to the end the implications of her own vision. “Maybe we should make him back into a teddy bear,” she says. No! I cry, and strike the table.

September 29th

I have met the man who is to do the voice of Barney. Bob West. His name is a poem. Tomorrow we begin shooting.

October 15th

I have finally achieved the opening shot. Barney stands in a wheatfield. The camera pulls back slowly to reveal the endless plains. Eight minutes into the reverse zoom, a wisp of smoke enters the edge of the frame. The wheatfield begins to burn, and in our last sight of Barney, before he is obscured by smoke, he makes an ambiguous gesture, one I remember well from a childhood dream. I am satisfied with the shot. However, Sheryl is unhappy at the number of wheatfields I had to burn to achieve it. She also argues that the introductory sequence will be too long to fit on a VHS tape, and leaves no room for the episode itself. She grows hysterical, complains of the mounting expenses, and waves a letter from her credit card company in my face. I am appalled at her pettiness. She does not understand the complexity of simplicity, how hard it is to do nothing when the world demands the lie of entertainment. We must concern ourselves only with the spiritual, but she is weak, weak. I have a severe pain in my little toe.

October 20th

Sergei tells me that the Soviet Board of Film has seen Sheryl Leach’s original scenario, and intervened to prevent my entering Barney for the Palme d’Or. This is intolerable.

October 28th

Today we burned the dacha in the forest. Barney wept and danced. Sheryl wanted to keep the dancing, but leave out the weeping and the burning of the dacha. We spoke strong words to each other. The actor who plays Barney is impossible. Somehow he has got his hands on a script. The extraordinary arrogance of the man! He wishes to know everything, as though he were the director. No! God was right, as He so often is; for an actor, the original sin is Knowledge. I wrote a new scene, in which he lies in mud for three days while wild dogs circle his weakening body.

November 12th

Sheryl has built a set in her kitchen. It consists of a number of cardboard boxes painted in primary colours. These are scattered around the kitchen table. She suggests the action take place at the kitchen table, climaxing with Barney standing, and making his way to the oven, to remove cupcakes and distribute them to the assembled children. In this I see something of the Last Supper. I grow excited, and I order Sven to light it in the manner of Caravaggio’s The Taking of Christ. Sheryl is resistant, arguing that we cannot see the primary colours in the candlelight, and that some of the local children recruited for this scene are afraid of the dark. She turns the kitchen lights back on.

I must remind myself, it is not her fault; she does not see what I see, the great panorama of the picture in its entirety. This sequence is to be followed by the long establishing shot of the Sitka Forest in winter, and the dying stag, its flanks withered by starvation, stripping the last bark from the sapling, killing it as he himself expires.

It is important that there is a continuity of effect across the cut, and I order another rain machine so that the rain which softens the moist earth in the Sitka Forest can begin to fall within this American kitchen. Sheryl argues that rain does not fall indoors. Clearly she has never dreamed. When her argument fails to sway me, she claims that it will cause further electrical problems and worsen the flooding in her basement. I urge her to be less concerned with the material world. She argues that I do not understand America. I argue that America does not yet understand itself. Barney tries to hit me, and I am forced to restrain him. Sheryl weeps, and begins to punch herself in the side of the head while singing “I love you, you love me”, over and over again.

The impasse is only resolved when the hire company refuse her credit card. I discuss the problem with Sven. We relight the scene, and instead film her tears as they fall on the cupcakes, dissolving the icing, while in the background the doctor tries to put Barney’s arm back in its socket. He screams. The effect is excellent. Perhaps our best day yet. The pain in my toe is almost completely gone.

December 9th

I ate today in downtown Dallas, in a popular Scottish restaurant. They serve a kind of modern haggis made from the intestines of beasts. After I had ordered the poetically named happy meal, the server silently gave me the gift of a small plastic toy. Extraordinary! This sensitive youth had seen the yearning child within. I wept, and embraced him. He wept also.

Then I ate, and read Tolstoy: “Death is an awakening. Dying early is like waking a man up when he has not had enough sleep. Dying old is when a man has slept his fill, and starts to sleep fitfully, and wakes up of his own accord. Suicide is a nightmare which finishes because you remember that you are asleep, and deliberately wake yourself up.”

So the only thing to decide is just how Barney will die, as the burning cathedrals sink into the lake—young, old, or at his own hand? Once we have decided that, all else will fall into place. I shall put this to Sheryl tomorrow.

(This is the final entry in the diary. Translated from the Russian by Julian Gough.)